Boston, MA — When an emergency arises during surgery, research has shown that surgical teams complete significantly more of the life-saving steps needed to manage the event if they use an OR crisis checklist than when relying on memory alone. Helping surgical teams reach for the checklists when a crisis arises requires a supportive environment and a good plan, according to a new study from Ariadne Labs and Stanford University.

The study, based on work funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality and published March 26 in Implementation Science, sought to better understand what helps and hinders successful use of OR crisis checklists and manuals at surgical facilities in the United States.

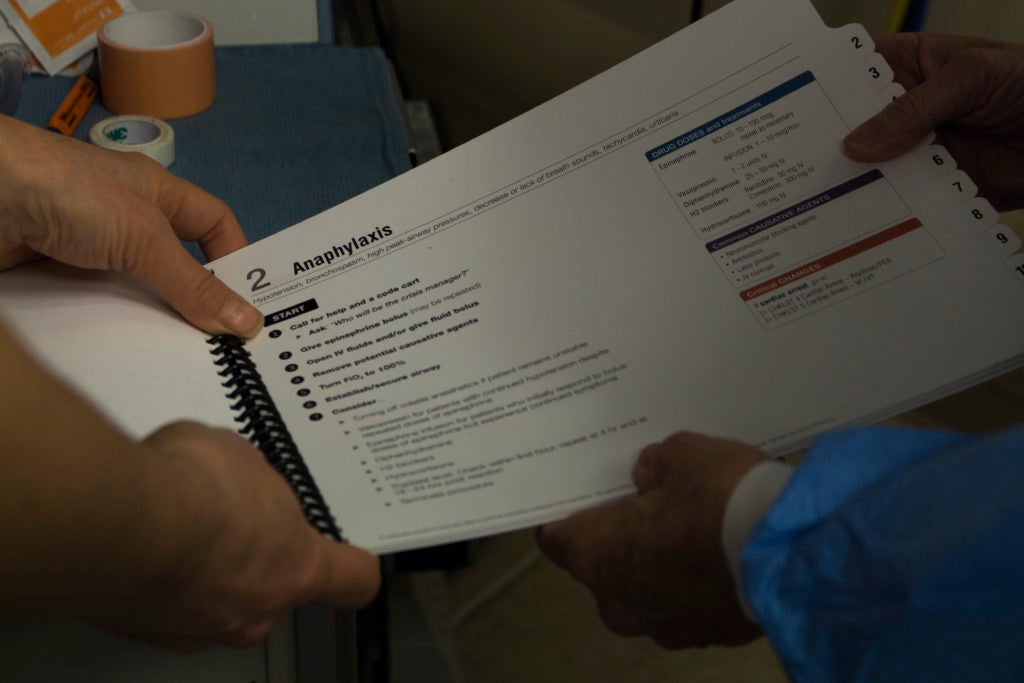

The study team surveyed clinicians who downloaded either the Ariadne Labs’ Operating Room Crisis Checklists or Stanford’s Emergency Manual: Cognitive Aids for Perioperative Critical Events. The findings suggest that having a clear, multi-step plan to introduce and encourage use of the tool and a supportive environment increases the likelihood the tool is used when it matters most. A supportive environment includes backing from department or hospital leadership and a well-respected colleague to champion the effort.

“This study is important because it offers a better understanding of what it takes to introduce a new initiative that improves care during an emergency,” says Dr. Shehnaz Alidina, a senior global health systems researcher at Harvard Medical School and lead author on the study.

That includes using the tools for things like training and debriefing sessions and not just during a crisis. “The more familiar clinicians are with the tools, the more natural it will be to reach for them in moments when it really counts,” said Dr. Bill Berry, associate director and interim chief implementation officer at Ariadne Labs and senior author on the paper.

When the rare OR crisis occurs, it requires a rapid, coordinated response from the surgical team to ensure the best possible outcome for the patient. Even though studies have shown that surgical teams are more likely to forget important steps when in an emergency or under stress, they have historically had to rely on memory to get them through critical events. This can leave the team unprepared to properly manage crises.

Checklists and manuals have long been used in other industries, like aviation and nuclear energy. Though these tools are relatively new to health care, there are studies that show their benefits. The World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist has been shown to reduce surgical complications and deaths. In one study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, complications dropped from 11 percent at baseline to 7 percent after the introduction of the checklist. Deaths dropped from 1.5 percent to 0.7 percent. When the OR Crisis Checklists were used in a simulation-based study, clinicians completed 93 percent of life-saving steps. Without the checklists, they completed only 77 percent of steps. Despite these known benefits, OR crisis checklists and manuals are not widely used.

The 368 U.S.-based respondents in the new study came from hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers ranging in size from one OR to more than 30. There was wide geographic representation in respondents, and most were anesthesiologists. More than half (54 percent) had more than 20 years of professional experience.

The study team found several factors were associated with regular use of OR checklists or manuals for crisis events:

- The more implementation steps the facility completed.

- The more ways the tool was incorporated into work outside of the OR.

- The more experience the facility had with other quality improvement initiatives.

- Having support from leadership.

- Having dedicated time to train staff on how to use the tools.

They also identified barriers to implementation:

- When clinical providers were resistant to the tool.

- When there wasn’t a clear champion of the work.

- When clinicians found the content and design of the tool unsatisfactory.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence showing that a supportive environment and clear implementation process are important factors when introducing a new tool. “It also surfaces some useful recommendations for others looking to introduce these types of tools or other quality improvement initiatives,” Berry noted.

Among the key recommendations for clinical teams noted in the paper:

- Dedicated training time. The study authors recommend that facilities secure dedicated time for surgical teams to become familiar with the tool and learn to use it effectively.

- Consider every suggested implementation step included in the survey when developing a plan to introduce the tool. The study authors argue that it is important to address all of the steps in some way and that doing so does not need to be a long, formal process in order to be effective.

- Use the tools outside of OR crises. Because critical OR events are so rare, it’s important for surgical teams to have opportunities to use and become familiar with the tools outside of crisis situations.

–By Margaret Ben-Or