By Evan Benjamin, MD MS and Tiffany Xie

Illustrated by Courtney Staples

In 1994, Betsy Lehman, a celebrated reporter for The Boston Globe, died of an overdose of chemotherapy. After a series of fatal mistakes from her care team, Lehman received four times the intended dose of chemotherapy, which led to her premature death at 39. The highly public nature of her story brought the national spotlight on the consequences of medical errors, and the backlash sparked a shift in how we approach patient safety.

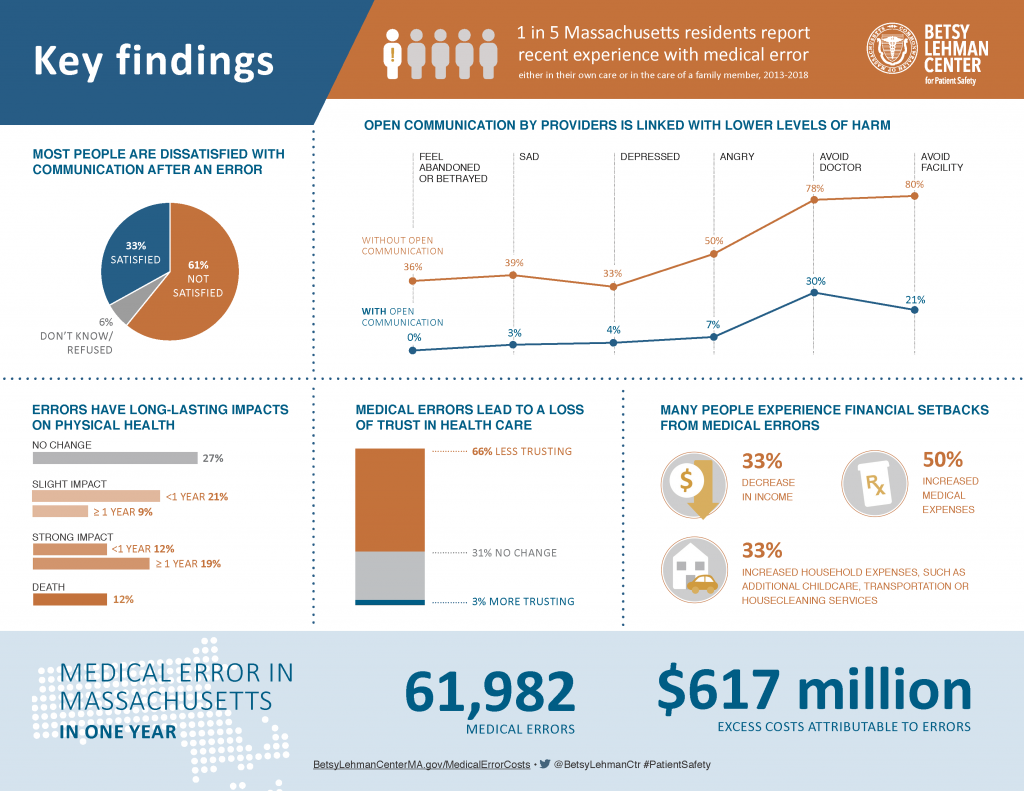

Lehman’s story ultimately led to the creation of the Betsy Lehman Center for Patient Safety of Massachusetts in 2004. This month, the center released a new report on medical error in Massachusetts demonstrating a continuing need for improvement. I had the honor of moderating a panel discussing the findings, which estimated that there were close to 62,000 medical errors in the state in one year resulting in more than $617 million in excess health care insurance claims. This figure is slightly more than one percent of the state’s total annual health care expenditures.

“Well, first thing [that would have helped] would have been to acknowledge and apologize that mistake had been made.”

Using survey methods, the report also captures patient perspectives: 20 percent of Massachusetts residents have experienced a recent medical error, and 75 percent of those residents did not receive support services afterward. Moreover, only 19 percent of those who experienced an error received an apology. As one patient noted, “Well, first thing [that would have helped] would have been to acknowledge and apologize that mistake had been made.” Most patients who received an apology believed that it was sincere. Finally, these apologies had a profound impact on individuals lives. When patients received a sincere apology, they were less likely to feel angry, depressed, abandoned, or betrayed.

If an apology is that meaningful after a medical error, then why aren’t more providers saying sorry? There are multiple barriers to apology in health care. Many providers are afraid that an apology is an admission of guilt that could lead to litigation. Fear of malpractice lawsuits leads to a culture of silence and “deny and defend” practices wherein hospitals withhold information out of fear. In spite of recent legislation in Massachusetts that promotes apology by making them in admissible in court, many providers still have fear. Providers are also emotionally uncomfortable to initiate apology conversations.

If an apology is that meaningful after a medical error, then why aren’t more providers saying sorry?

Recent events demonstrate an increasing intolerance for this kind of behavior. After the backlash from the #MeToo movement and the Boeing 737 Max plane crashes, it is clear that the public call for transparency extends across societal issues.

We live in a world that increasingly demands not only an apology, but also a commitment to improvement. We should demand the same from our health care. Deny-and-defend practices not only sow mistrust between patients and providers, but fail to improve care to prevent the same mistake from happening again.

A promising alternative to “deny and defend” strategies lies in communication and resolution programs (CRPs). In these programs, providers transparently communicate to patients about what happened and offer fair compensation to patients and families. This communication also extends to the system itself so preventable mistakes are not repeated. Unlike deny-and-defend strategies, this approach ultimately fosters respect, healing, and learning about the root causes of medical error.

[The communication and resolution] approach ultimately fosters respect, healing, and learning about the root causes of medical error.

Studies have concluded that CRP programs promote healing of patients and providers (Moore et al. 2017) and are not associated with more lawsuits (Mello et al. 2017, Kachalia et al. 2018). At Ariadne Labs, we are working to share this model nationally. We have collaborated with the Collaborative for Accountability and Improvement to develop metrics and improvement strategies to help health systems create and improve communication and resolution programs. We are also developing new tools to help implement communication and resolution practices in hospitals nationwide.

In healthcare, an apology is only worth as much as its impact on patients. “Sorry” is not enough. It is only the start.

Evan M. Benjamin, MD, MS, is the chief medical officer at Ariadne Labs and Associate Professor at Harvard Medical School. This blog was co-written by Tiffany Xie, an intern for the Office of the CMO at Ariadne Labs.