By Ian Solsky, MD, MPH

Illustrated by Courtney Staples

Attending medical school more than 30 years ago, my father claims he worked with a surgeon who gave trainees feedback while brandishing a pistol and stomping on the eyeglasses of a student that had slipped into the surgical field. As a general surgery resident, I can report that my colleagues today have far better communication and teamwork skills. However, I have witnessed echoes of this behavior — surgeons throwing supposedly dull instruments across the operating room, having tantrums over trivialities, and not knowing the names of the staff they work with or the patients they operate on. In a time of heightened sensitivity to workplace behavior, surgeons should seriously think about the culture they are fostering.

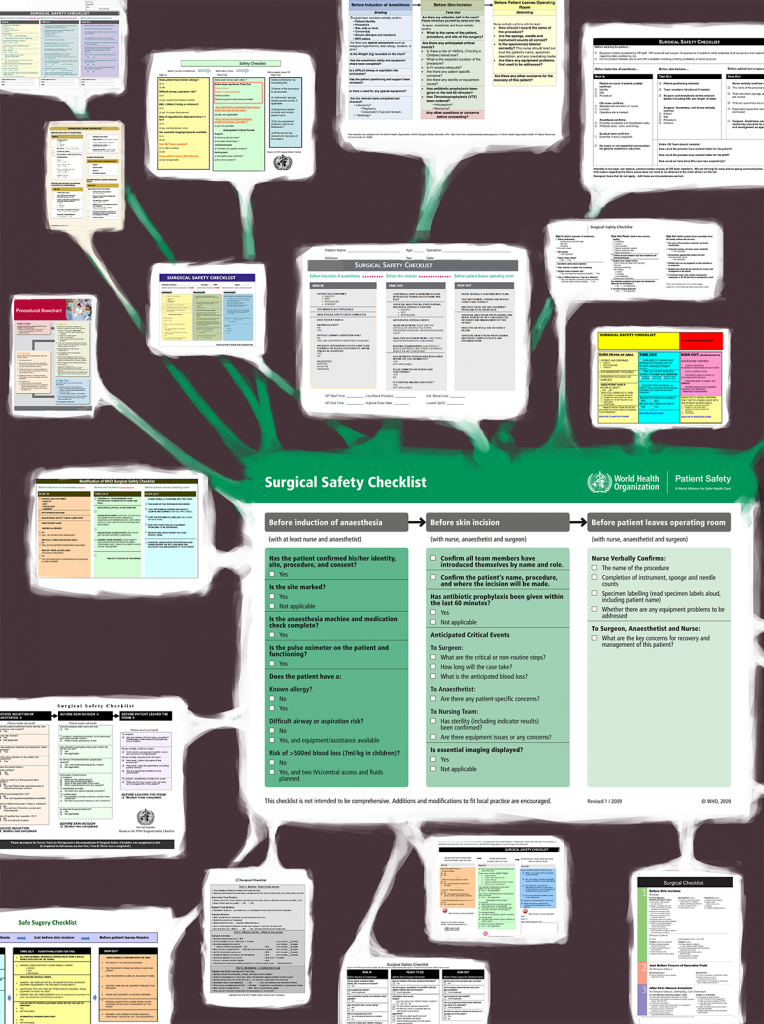

I had the unique opportunity to delve into this culture as an Ariadne Labs surgical fellow contributing to a study analyzing modifications made to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Surgical Safety Checklist. After examining hundreds of checklists, I realized that each was a window into a different OR culture, revealing variable attitudes toward teamwork, communication, and safety. The good checklists were clear and simple, empowered all team members, and modified to accommodate local workflow. The bad ones looked like abstract art: they were cluttered with too many items, images, and colors arranged in confusing ways that made them difficult to use.

The good checklists were clear and simple, empowered all team members, and modified to accommodate local workflow. The bad ones looked like abstract art: they were cluttered with too many items, images, and colors arranged in confusing ways that made them difficult to use.

The intent of the WHO checklist is to make surgery safer globally. Ten years ago, the annual number of deaths from preventable medical error was described as equivalent to a jumbo jet crashing each day for a year. The need to prevent these errors prompted Ariadne Labs to lead a global effort to standardize checklist use globally. In 2008, the WHO adopted it as the global standard of care. Nearly 10 years of data show that the checklist reduces morbidity and mortality when implemented properly. Most recently, Scotland saw a 36 percent reduction in post-surgical deaths since implementing the checklist as part of a national health safety program.

Comprised of 19 items critical to patient safety, the checklist is not merely a memory aid ensuring that the correct person is operated on and correct organ removed; it is intended to improve communication and teamwork. The WHO encourages additions and modifications of the checklist to address local needs, create a sense of ownership, and foster hospital level buy-in. In our analysis of 155 checklists used globally, we found that every checklist was modified, often with items of questionable value like those referencing administrative tasks. Others removed items critical for fostering teamwork and communication, including items from the “anticipated critical events” section (sometimes called the “time out”) in which all team members have an opportunity to discuss concerns and ask questions.

In our analysis of 155 checklists used globally, we found that every checklist was modified, often with items of questionable value…Others removed items critical for fostering teamwork and communication.

From these findings, we made several recommendations for checklist modification practices, including:

- creating a multidisciplinary team;

- assessing current OR practices;

- designing a checklist with as few items as possible and a logical format;

- testing modifications prior to implementation; and

- establishing a plan to update the checklist as needed.

Our results also lent some insight into how checklist use can help modify surgical culture.

Surgeon resistance is frequently cited as a barrier to checklist implementation and we hypothesized that this was behind the removal of items about teamwork and communication. This response is understandable since surgical personalities can clash with what the checklist demands. Surgeons are expected to be efficient while the checklist can appear time-consuming without proper engagement and communication from all. Surgeons are outcomes-focused; without the instant gratification of an operation like removing a cancer, skepticism about the checklist’s benefit can creep in. Surgeons seek perfection while the checklist recognizes fallibility. Surgeons are often trained to be independent while the checklist is designed for teams.

Improving surgical culture, however, does not require a new breed of surgeon. Like slight modifications to the checklist, these personality traits simply need to be tweaked:

Surgeons should always strive for precision and efficiency in the OR, but they should do so for the entirety of a case, including the period before the incision when the checklist begins, during the time out, and after.

The checklist gives an opportunity to set the tone for the room, and it can be an effective way to foster patient safety and provide the surgical team with feedback.

Surgeons will always be goal-oriented, but they should think about outcomes on larger scales over longer time periods.

Each surgeon is part of a larger health system and contributes in a way that helps or harms patient safety efforts on a population level. Furthermore, each case that a surgeon performs is an opportunity to nudge surgical culture in a positive way — inspiring trainees, medical students, and other staff with actions that promote communication and teamwork.

Surgeons should not aim for perfection but for constant improvement.

The checklist can teach us to be humble and cognizant that error can happen to anyone, that we must constantly learn from mistakes, and that we should strive for the highest quality care for every patient every time everywhere. The quest for mastery of technical skill should accompany efforts to eliminate iatrogenic error.

Surgeons should be capable of independence but should not actively seek it.

The process of becoming a surgeon is never-ending and those at all levels have the capacity to educate, assist, and learn. The checklist promotes this mentality by inviting everyone to engage in being vigilant and giving everyone permission to speak up during a case.

Individual surgeons should appreciate that, like the checklist, they may have to modify their personality and approach for different situations and teams to achieve the best outcomes. Through proper checklist modification and use, they will promote the ideal principles of teamwork and communication for our patients’ safety and improvement of our workplace.

Ian Solsky was an Ariadne Labs surgical fellow and is currently completing his general surgery residency at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City.