Published May 28, 2021 (Updated: September 28, 2021)

In March 2021, Ariadne Labs launched the Global Mass Vaccination Site Collaborative to facilitate a rapid information exchange to broaden the impact of and safely deliver more COVID-19 vaccinations globally. Fifty members representing more than 12 mass vaccination sites from across the country began meeting regularly, sharing information, and comparing notes on the effort to get shots into as many arms as rapidly as possible.

The meetings became lively forums on topics ranging from the logistics of directing hundreds of cars in stadium parking lots to efforts to reach vulnerable people right in their communities. Participants spoke frankly about their successes and their challenges, about what they learned, and what they would focus on next time.

“Next time” is the operative phrase. While some countries are making headway against the COVID-19 virus, others are struggling. Even if mass vaccination sites may soon close in the United States, the effort to inoculate the world is still ongoing. “We can’t afford to assume that this is a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic,” said Eric Goralnick, MD, MS, Associate Faculty, Ariadne Labs and Principal Investigator of the collaborative. “We want to share our insights, learnings, and practices with the hope that they will be useful now and in the future.”

Initial Global Mass Vaccination Site Collaborative members include (in alphabetical order):

- Atrium Health, which has held mass vaccination events at Bank of America Stadium and Charlotte Motor Speedway, as well as establishing innovative roving vaccination sites for underserved and rural communities, to ensure equitable access.

- Bellin Health, which operates the Lambeau Field Community COVID-19 Vaccination Site in partnership with Brown County Public Health and the Green Bay Packers.

- The Canada International Scientific Exchange Program (CISEPO).

- CIC Health, which operates mass vaccination sites in Massachusetts at Gillette Stadium, the Reggie Lewis Center, and Hynes Convention Center (the latter currently in partnership with FEMA). Mass General Brigham provides medical direction for all CIC Health vaccination sites.

- CORE (Community Organized Relief Effort), which operates sites at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles alongside its partners at the City of Los Angeles, LAFD, and medical partners Carbon Health, Curative, and USC School of Pharmacy. CORE also staffs the Mercedes Benz Stadium in Atlanta, in partnership with AFCEMA of Fulton County.

- The State of New Hampshire, which operates the New Hampshire Motor Speedway Mass Vaccination Site in partnership with Regional Public Health Networks, and local police, fire and EMS, and hospitals across the state.

- UCHealth, which operated the mass vaccination site at Coors Field in partnership with the Colorado Rockies, Denver Police Department, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, City and County of Denver, and Verizon — and continues to offer vaccines to up to 40,000 people a week at its 11 locations across Colorado.

- UC San Diego Health, which operated the Petco Park site and maintains a site on its campus.

- Metro Public Health Department, which operates mass vaccination clinics in Nashville, TN, in partnership with Meharry Medical College, the Music City Center, FEMA, U.S. Forestry Service, Nissan Stadium, and the Tennessee Titans.

This blog has been launched as a way to record and share the learning and insights gained from this collaboration. Below are narrative summaries and key takeaway points from each collaboration meeting.

Lisez ceci en français version.

Table of Contents

Boost and the Effort to Support Vaccinators Around the World

What the Numbers Tell Us about Vaccine Equity

The Complicated Effort to Reach Those Reluctant to Get the COVID-19 Vaccine

How Do We Reach Vaccine Deserts?

Could Schools Be A Vital Link for Widespread Vaccinations?

Bottom Up, Not Top Down, Will Be Solution to Vaccination Efforts in India

Incentives and Disincentives for Vaccination

Shifts in Vaccination Focus: International and Children

Assessing Risk on a Plane — As You Fly It

Fear? Football? Free drinks? Freebies? What Motivates People to Get Vaccinated

Be Our Guest: Turning Vaccination in an Experience

The Rules of Engagement for U.S. Military in Emergencies or Medical Crises

Coping With an Ever-Changing Vaccine Landscape

Dream Helps Solve Potential Nightmare

Charlotte Motor Speedway and Bank of America Stadium: >36,000 vaccines in less than 10 days

CORE Tackles Vaccinations From Mass Sites to Mobile Units

Kickoff Meeting Delves into Logistics of Nashville Event that Vaccinated 10,000 in a Day

Boost and the Effort to Support Vaccinators Around the World

Oct. 8, 2021

The push to vaccinate the world against COVID-19 is just the latest wrinkle in the global effort to bring the pandemic to an end. Since 2013, the initiative now known as Boost (formerly called the International Association of Immunization Managers) run by the Sabin Vaccine Institute, has been working to empower immunization professionals in their careers and their communities and is now adapting its learnings for this latest pandemic.

What was particularly striking to members of Ariadne Labs’ Global Mass Vaccination Site Collaborative, who heard a presentation by Boost during the collaborative’s Oct. 8, 2021, meeting, was how Boost aimed to empower immunization professionals to play key roles in their community’s public health.

“People are searching for ways to do things differently and more effectively,” said Yvonne Akukwe, MPH, Boost Manager of Global Learning and Engagement.

In April 2021 Ariadne Labs launched a vaccination collaborative to facilitate a rapid information exchange about the delivery of COVID-19 vaccinations. The collaboration included public and private organizations such as hospitals, health-care systems, health departments, and non governmental. The collaboration meets weekly to discuss a range of issues related to vaccine delivery, from setting up vaccination sites on racetracks and football stadiums, to building vaccine confidence, to the challenge of immunization efforts in India, Canada, Brazil, and Haiti.

Akukwe and Jennifer Fluder Siler, Sabin’s vice president of Global Community Engagement, met with the collaborative to introduce their organization and discuss global efforts to increase vaccine uptake.

“Our mission is to foster a global community that enables immunization professionals to connect with peers and experts, learn skills that build capacity and advance careers and lead immunization programs in challenging contexts,” Siler said.

Boost made a targeted pivot in 2019 from a focus on national immunization staff in high- and low-income countries to a focus on national and sub-national immunization staff in low- and middle income countries, as its teams confronted huge problems with isolation among immunization professionals responsible for thousands of doses for a variety of conditions. Boost saw that lines between immunizers and public health were blurring, and there was a need to establish immunization as a career track. They “found burnout and fatigue and no particular support on the ministry of health side; people will go months without getting paid and stay dedicated,” Siler said.

The initiative created and now nurtures a space where people can learn not only technical skills but also skills in leadership, advocacy, and community organizing. The platform provides curated resources, tools and access to webinars. Public and private learning groups bring together like-minded professionals. Currently the organization has about 1,780 active profiles in 132 countries.

To promote empowerment, Boost offers online courses in Adaptive Leadership, including an introduction class on the concept and a six-week intensive course on “Boost Scholar Course: Adaptive Leadership for Immunization.” “It changed the mindset of what it means to be a leader and how to lead in the future,” Akukwe said.

Other courses zero in on foundational capacity building — the focus is not on traditional advocacy, which usually involves well-trained experts speaking on behalf of people in need, but on community organizing, which develops and builds the cooperative power of the community itself to address challenges.

Another Boost course is “Storytelling for Change,” a self-paced course that provides an opportunity for members to learn new skills to generate public emotion, value and action on a social issue.

Two months after the organization relaunched as Boost, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, pushing Boost to adopt a more bottom-up and not top-down approach and underscoring the need for community engagement. As part of its COVID-19 Vaccine Equity Project, Boost launched the COVID-19 Listening and Learning Series — a platform for immunization professionals as well as others involved in COVID-19 vaccine delivery to share their perspectives on vaccine introduction with particular emphasis on transferable lessons learned — the series includes a podcast to provide insights from the frontlines of COVID-19 vaccine site globally as well as feature experts to answer questions on the vaccines. Upcoming is a podcast with Right to Care on vaccine delivery learnings from their rollout in South Africa. “We are trying to source from around the world as many real-time learnings as we can,” Siler said.

“Boost’s leadership in the vaccination community in low- and middle-income countries prior to the pandemic significantly strengthened systems as they expanded to larger scale roll outs of COVID vaccinations. We are excited to partner with Boost during the next phase of our collaborative,” said Eric Goralnick, MD, MS, Associate Faculty, Ariadne Labs, and Principal Investigator of the Global Vaccination Site Collaborative.

Key Takeaways:

- Provide a platform for immunization professionals and other health professionals involved in vaccination efforts to share perspectives.

- Creating two-way conversations so that immunization staff can reach and support each other, and experts. Make sure immunization staff at all levels “feel heard.”

- When creating incentives for immunization, know your audience and proceed appropriately.

- Enhance equitable vaccine delivery by identifying areas that would benefit from additional country-level support.

- Utilize adaptive leadership and community building capacity building at all levels in the immunization system to move organizations, communities, and teams beyond the status quo.

- Utilize the power of narrative and storytelling to advocate for change.

What the numbers tell us about vaccine equity

Aug 27, 2021

Benjamin D. Trump, PhD, a research social scientist for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, began his presentation to the Global Vaccination Site Collaborative on his efforts to document inequities in COVID vaccination as he would a military briefing “with the bottom line up front.”

There is, he first acknowledged, “no such thing as perfect data collection with COVID.” Too much of the reporting remains incomplete.” Yet utilizing census data, the initial supply chain for vaccines, and other information, Trump was able to create a portrait of where the United States stands in terms of working toward achieving herd immunity.

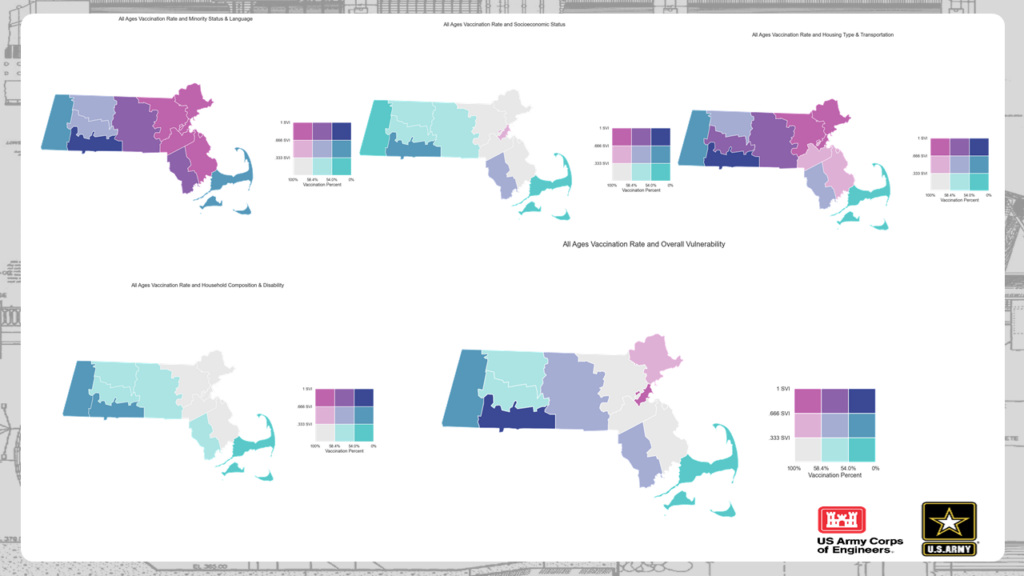

Since March 2020, at the behest of FEMA, Trump and Dr. Igor Linkov, a senior scientific technical manager with the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center, have worked to create a methodology to assess and compare vaccine equity within and across regions. President Biden has asserted that equal opportunity in vaccine access is critical to COVID-19 recovery. Public health officials need ways to benchmark and prioritize information to promote equitable access.

Trump and team focused on three questions: Does vaccine inequity exist, where does it exist, and why does it persist? The answer to the first question was clearly “Yes,” and data could pinpoint inequity county by county. As for the “why,” Trump discussed the issue of “vaccine hesitancy as a proxy for lack of access because the data for the latter is not great.”

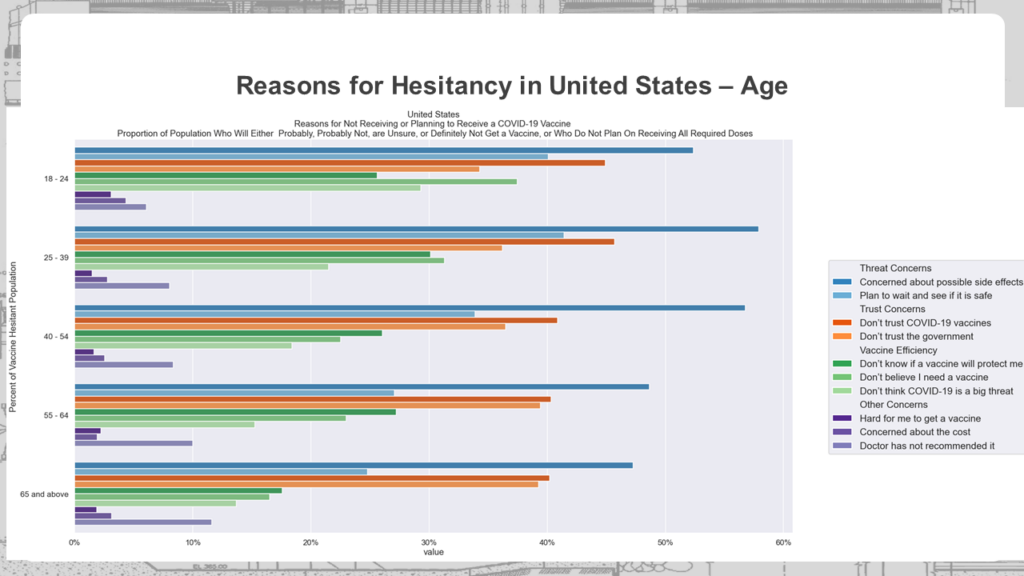

Hesitancy has been decreasing in response to the Delta variant, but hesitancy remains high in the subgroup of individuals who have only received the first shot of the two-shot vaccines, Trump said. This group is small but poses worries for achieving herd immunity. There are “an awful lot” of reasons for hesitancy, he noted, but chief among them is the fear of side effects. Others adopt a “wait and see” attitude about the vaccine’s safety over time, a concern that may not be mitigated by the FDA’s recent approval of the Pfizer vaccine. Others simply mistrust the government.

As Julie Rosenberg, MPH, Assistant Director of Project Management, Better Evidence at Ariadne Labs, noted in the Zoom chat, Washington State data from unvaccinated groups indicated that FDA approval won’t change their intentions as they have overall lost trust in the FDA based on its speed and handling of the vaccines. Another collaborative member in the chat noted that religious conviction may have an effect as “some religious/spiritual individuals have not yet received an individual instruction from God to get vaccinated.”

There also is confusion over the difference between infection and hospitalization rates and thus over the vaccine’s efficacy. “A good amount of folks are saying, ‘Maybe I don’t need the vaccine,’ ” Trump said. Many conflate the concept that “boosters will help efficacy” with “vaccines don’t work at all.”

People with higher incomes tend to be more vaccinated; vaccination rates decline with income as low-income, single-parent households, and young individuals without insurance worry about losing pay because they would have to miss work to get vaccinated. Using the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index, Trump’s team found areas of vaccine inequity in places with issues with housing and transportation, thus pinpointing opportunities for closing gaps.

Eric Goralnick, MD, MS, Associate Faculty, Ariadne Labs and Principal Investigator of the Global Vaccination Site Collaborative, praised Trump’s meticulous presentation and commented that the information was like “snapshots in time.” He asked Trump if he had thought about mapping out the impact after policy changes. “We have definitely thought about it,” Trump said, indicating it is a question his team would be interested to explore. Becky Fox, MSN, RN-BC, of Atrium Health also wondered about the community-wide effect of local school mask policies. Trump said this might also be tracked.

While numbers don’t tell the whole story of COVID-19, this data could be used to develop effective strategies to promote further uptake of the COVID-19 vaccines.

Key Takeaways

- Vaccine hesitancy has many roots but the dominant one is fear of side effects.

- Those who adopt a “wait and see” attitude will be much harder to convince than those concerned about side effects.

- The Delta variation is having an effect on decreasing hesitancy.

- More education is needed about infection rates versus hospitalization rates to show that the vaccines are, indeed, having an effect on saving lives.

- A high Social Vulnerability Index seems correlated with a lower vaccination rate, which may help to devise more effective interventions.

COVID Campaign 101: How Holy Cross Used the Spirit of Competition to Achieve a 90-plus Percent Campus Vaccination Rate

Aug 20, 2021

One of the looming challenges in mitigating the spread of COVID-19 and its variants is the return of thousands of college students to campuses around the country this fall. Many universities and colleges require students to be vaccinated and tested weekly; others are taking additional steps to prevent outbreaks on campus and in nearby communities. Yet concerns linger about COVID-19 outbreaks among students.

An example of a successful campus COVID-19 vaccination effort was highlighted at the Aug. 20, 2021, meeting of the Global Vaccination Site Collaborative. Presenters illustrated how a carrot-and-stick campus vaccination campaign at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass., resulted in more than 90 percent of the student body getting the vaccine.

Liz Drexler-Hines, MPH, director of Student Wellness Education, and Kelsey DeVoe, FNP-C, director of Health Services and a nurse practitioner, presented on the efforts at Holy Cross, an undergraduate college of about 3,000 students, about 57 percent of them from outside Massachusetts.

In fall 2020, Holy Cross students, like many college students, were taking classes remotely. In spring 2021, they returned to in-person classes and dorm life. Even before vaccines were available to college-age students, a community-wide education program on vaccinations was launched. On May 1, 2021, the first vaccine clinic was held, and about 400 were vaccinated. Some students took the initiative to go home and get vaccinated; others said that “they would get around to it,” said DeVoe.

Drexler-Hines said she consulted directly with students themselves to come up with incentives for a major campus vaccination push. “The students and I spent a long time breaking down the headlines and trying to target misinformation and putting school policy in easy-to-grasp language,” she said. They opted to create a campaign that would emphasize how vaccinations would allow students to mingle and socialize – something disallowed the previous semester. Students were also worried about the timing of the vaccines – for example, if they got a shot and fell ill during finals. In response, on-campus clinics – allowing walk-ins without appointments – were held and proved to be popular. Students were particularly happy and comforted to see campus health officials were running the vaccine clinic. Students realized “they were making their home safer,” DeVoe said.

Another successful technique was the use of student health ambassadors, or volunteer peer educators. About 30 students were trained to regularly engage in encouraging health behavior, how to navigate difficult conversations, explain campus policy, and provide hand sanitizer and masks.

In weekly meetings, core ambassadors filed reports which allowed the school to keep track of what was going on under the surface, such as problematic off-campus parties, Drexler-Hines said. The ambassadors, who worked with students one-on-one, quickly developed their own sense of community. Even so, from August 2020 to May 2021, about 300 students tested positive for COVID-19, about 600 students were placed in quarantine, there were four dorm lockdowns, and two campus-wide lockdowns.

Later in May 2021, a vaccine mandate was announced, with a July 15 deadline for at least one dose. But Holy Cross health officials wanted to incentivize students, not just punish them with expulsion. So they came up with campus-wide vaccination “challenge” to ensure a high vaccination level. “We asked students: ‘What are you most looking forward to if we can end COVID restrictions?’” said DeVoe. In addition to generally missing being together, students noted that they were sad that a concert planned for the spring semester had been cancelled.

So the HCOurShotChallenge was launched. If the campus could collectively reach 90 percent of the population having uploaded documentation of at least one dose by July 15, a fall concert would be held. The first class to hit 90 percent would also win a coveted VIP food truck experience. A large boost in posting vaccination documents followed. On June 25, a simple yet visually appealing dashboard was created, and 50 percent of the students reported at least one vaccination. With reminders, videos, and social posts, vaccinations for the campus community reached 82 percent by July 14, a day before the deadline.

Text alert reminders to get vaccinated were sent. By 9 a.m. on July 15, the total was 89 percent; the senior class hit 90 percent first. By 1:45 p.m. the campus reached 90 percent. Currently the campus is at 96 percent of students having one dose and 92 percent fully vaccinated. About 100 students applied for waivers.

“Our contest really had a large impact on our students,” DeVoe said. “The biggest boost we got was when we pulled in the students and asked, ‘What do you need to be vaccinated?’”

“But then: Delta.”

By July 20, the campus had its first breakthrough COVID-19 case from a vaccinated person who had been traveling. On Aug. 16, an indoor mask mandate was re-instituted, which made students – who had been told “Get Vaccinated and You Won’t Have to Wear a Mask or Be in Quarantine” – feel a bit like they had been subject to a “bait and switch” trick.

“We really had to work on our communications,” DeVoe said. “We announced the mask mandate without any explanation so we had to follow up and explain that we need to have a safe start.”

She hopes that there will be an easing of restrictions as time goes on, although the situation with boosters adds another complication. The campus will host both flu and COVID-19 vaccination clinics monthly. “Holy Cross will be a pretty safe place to be this fall,” DeVoe said.

Key Takeaways for Campus Vaccination Campaigns

- Keep it simple. Have easily recognizable incentives for vaccinations.

- Work with partners and stakeholders, such as student government leaders, the college communications department, student ambassadors and senior administrators.

- Meet students where they are – which is usually by social media and text messaging. Parents read emails – students are more likely to read texts.

- Positive peer pressure really works, even with young adults.

The Complicated Effort to Reach Those Reluctant to Get the COVID-19 Vaccine

August 13, 2021

In early spring, even as Americans lined up for the newly available COVID-19 vaccines, a group of Harvard Medical School (HMS) students and researchers at Ariadne Labs saw change looming. Very soon, they knew the clamor for shots would slow down and instead there would be a clamor to reach those reluctant to be vaccinated. In anticipation of this, they launched a multi-faceted project to determine how to reach out to those with questions about getting vaccinated.

The sequence of events that led up to release of the COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence Toolkit in May, 2021, were presented to the Aug. 13 meeting of the Global Vaccination Site Collaborative, and produced a lively discussion on ways to face vaccine resistance and hesitation.

“When the vaccine first appeared, the demand was greater than the supply; things were moving quickly and people on the front lines were trying to get immunizations,” said Chief Medical Officer at Ariadne Labs, Evan Benjamin, MD, MS, FACP, who was among the group that created the Vaccine Confidence Toolkit. “But we anticipated that things were going to change — that we would likely see demand fall and there would be a significant number of people who were lacking confidence or had questions about the vaccines.”

HMS students and researchers at Ariadne Labs, which has pioneered conversation guides for helping people make health-related decisions such as the Serious Illness Conversation Guide, began pondering the best path forward.

What does vaccine hesitancy actually look like? What are people’s specific concerns about the vaccine? What do we know about the vaccines and their side effects? And who do people trust to give them clear, accurate information about the vaccine?

Researchers examined the available literature and quickly concluded that the vaccine hesitant were “not a monolithic group” in terms of demographics or even degree of hesitancy, said Kristi Hill, a fourth year HMS student. “It is really important to distinguish between people who are hesitant and have some ambivalence about the vaccine from those who are resistant, saying they absolutely will not get the vaccine.” Research suggests you are more likely to have success convincing the ambivalent population, which constituted the greatest percentage of those who are not sure about vaccination, Hill said.

So what was the best way to reach this group? Research indicated family friends and health care providers were the best messengers and personal physicians would be most effective. Examination of motivational literature indicated the more effective approach was creating an open and caring environment to elicit the patients’ concerns. Thus, primary care physicians should be clear and transparent when answering questions.

Carl Lawrence, a recent HMS graduate and current pediatric resident at Mount Sinai Hospital, described how, after initial feedback, a conversation guide about vaccines and a baseline fact sheet were developed and distributed to care providers for two more rounds of feedback. He noted how quickly new information and studies about the vaccines became available, prompting the team to focus on more immutable facts and strategies to dispel myths. The final toolkit had a conversation guide, a visually appealing patient handout, and list of external resources. “The handout does not have complicated scientific language that a patient would not understand,” he said. Lawrence prefaced his comments by acknowledging that during his evening clinic, he had no luck in convincing a patient to get vaccinated, saying with a sigh, “It’s easier said than done, but we try.”

The COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence Toolkit, which is both web-based and contained in a downloadable PDF, has been shared widely with a variety of organizations. Thus far, there have been 15,00 social media impressions; 2,000 direct toolkit views; and 402 toolkit downloads. Unfortunately, the Delta variant has raised new concerns. “The misinformation pipeline is changing. There’s new misinformation out there,” said Benjamin.

The collaborative’s follow-up discussion focused on creating partnerships, such as with the National Association of County and City Health Officials; how to increase the volume of toolkit uptake; the impact of breakthrough infections; and the burgeoning multifaceted reasons people give for not getting vaccinated.

“The rebuttals (to vaccination) I get are similar, the problem is there’s an infinite number,” Lawrence said. “It has not been a question for me of one discreet fact. It’s a constellation.” Another difficulty: Questions may be pointed and appropriate but answers may be nuanced, particularly on issues like transmissibility, he said.

“We have to be very good listeners and find that middle ground, find that ‘yes,’” said Eric Goralnick, MD, MS, Associate Faculty, Ariadne Labs and Principal Investigator of the collaborative. “We have to commit to learn from each other what works and doesn’t work in these conversations because this is new ground for all of us.”

Key Takeaways

Vaccine hesitancy is found in a wide swath of demographic groups. Those who are more concerned about COVID and who had flu shots in the past were more likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine

- Vaccine reluctant involves many factors but can be generally divided into these areas:

- Safety and side effects; they may have had bad experience with previous shots.

- Efficacy. Will it work as promised?

- Concern about the speed in which the vaccine was developed. Was it rushed?

- General mistrust of the government and health care system

- Personal physicians can be trusted messengers but there are others, including community and religious leaders.

- Reasons for declining a vaccination may be multifaceted; there is often no one fact or piece of evidence that will be convincing.

- Every reluctant person who agrees to a vaccination is a victory and should be celebrated.

How Do We Reach Vaccine Deserts?

August 6, 2021

One of the roles of Ariadne Labs has been to think ahead and find, compare, and evaluate relevant data sources in order to develop useful tools for equitable access to health care. One of those tools has been the Vaccine Equity Planner, developed by Ariadne Labs, Boston Children’s Hospital, and Google, which presents potential vaccination sites, population characteristics, and area-based measures within vaccine deserts by combining public data sets.

On August 6, 2021, members of the Global Vaccination Site Collaborative heard a presentation about the Vaccine Equity Planner from one of its designers.

Rebecca Weintraub, MD, who leads Ariadne’s Better Evidence program and the labs’ Vaccine Delivery Team, described the purpose of the tool and demonstrated its functions. The aim of the tool is to identify COVID-19 “vaccine deserts,” based on travel time via different modes of transportation (driving, walking and public transit), to show decision makers where further intervention is needed

Weintraub reminded the group that for some, getting vaccinated might mean taking time off work, finding child care, and riding public transportation for 30 minutes or more for each dose. For others, the walk or drive is simply unattainable.

Since the beginning of the vaccine rollout, both storage and wastage requirements have changed. “For example, the FDA has now approved that the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines can be stored in a regular refrigerator for a month,” Weintraub said. “But there is an information lag; we need to disseminate updates and encourage providers to store vaccine supply — so it is available in the midst of outpatient care. The vaccine should always be on the menu.”

With the Vaccine Equity Planner tool, it is possible to identify vaccine deserts as well as locate potential vaccination sites within these deserts. The tool can display counties by Social Vulnerability Index, shade counties by the number of people who intend to get vaccinated but are not yet, and define deserts based on transportation distance and travel time. Users can also download site contact information. The tool is updated weekly to track changes in site location and spread of vaccine deserts.

Throughout the pandemic, under-resourced public health organizations have had difficulty finding accurate and granular data. Leaders continue to face uncertainty. Tools like the Vaccine Equity Planner can augment how public sector leaders are adjusting their vaccine rollout by giving them anonymized and aggregated data-driven insights, down to the zip code level, to ensure access, availability and equity.

Key Takeaways

- The Vaccine Equity Planner tool identifies vaccine deserts, where people have little or no convenient access to vaccination and potential new vaccination sites to address the gaps.

- Some barriers that interfere with reaching and supporting vaccine deserts include time, distance, and cost limits, as well as vaccine storage and wastage.

- It is essential to locate these vaccine deserts and address the need for potential sites in order to improve access and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine on a federal level.

Could Schools Be A Vital Link for Widespread Vaccinations?

July 30, 2021

Schools in the United States have been thought as the great equalizer of American society, even if they often fall short of that lofty goal. Now schools could play a pivotal role in equalizing access and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccinations. During the July 30, 2021, meeting of the Global Vaccination Site Collaborative, members heard a presentation on the School Vaccine Hub, which was launched early in 2021 to provide school communities with a central source of information and resources about COVID-19 vaccines from trustworthy medical and public institutions.

School Vaccine Hub representatives Eric Tucker, DPhil, MSc, co-founder and Executive Director of Brooklyn Laboratory Charter Schools, and L. Arthi Krishnaswami, founder and CEO of RyeCatcher and the Community Success Institute, explained how the site addresses what Tucker called the “two Americas.”

“As the struggle with COVID wanes in some parts of the country and grows in others, what we’re seeing is a bifurcation (into) two Americas,” Tucker said. This may produce a split between school systems in which some will resemble the problematic systems of last winter, while others in communities with high vaccination rates will be on track to better and safer learning.

How, then, to equalize these two systems? A key part of the hub’s approach is to view those who have not been vaccinated as falling into different groups: “Those under 18,” “Covid Skeptics,” “System Distrusters,” “Limited Access,” and “Wait and See.” “Our belief is that the school communities around the country – including extended family members of students and staff – have the ability to address each of the populations that are currently unvaccinated,” Tucker said.

A school-based vaccination program can particularly address the under 18 population and those lacking access to vaccines. Kindergarten and science teachers can also leverage their status to be reliable and trusted sources for vaccine information, Tucker said. “One of things that we encourage schools to do is listen and understand vaccine hesitancy.”

The School Vaccine Hub has become a source for curriculum on COVID-19, on actions schools can take, and for reliable and vetted information that is regularly updated and targets misconceptions or misinformation. The hub also identifies strong vaccine providers and promotes the Vaccine Equity Planner as a tool. The site also provides resources and support for organizations running vaccination campaigns.

“Schools need to communicate with their students and families in a host of different ways. When sharing information, it’s hard to have those conversations and it’s hard to have them in a structured way,” said Krishnaswami. “So last year Brooklyn Lab started to provide a set of template guidelines to help with emails, communications, and newsletters and we are now updating them based on changes in the last year.”

Additionally, “we want to amplify positive stories,” so they are writing case studies and other narratives that can be shared through social media, Krishnaswami said.

The School Vaccine Hub representatives spoke of their hope that school buildings and physical facilities – stable, familiar public places – can be used to function as community vaccination sites, a process with which members of the collaborative were experienced. Schools could step into the vacuum left when participation dropped for mass vaccination sites.

“We believe strongly in the role that schools can play, having mapped them out in all the (vaccine) deserts,” said Julie Rosenberg, MPH, Ariadne Labs Assistant Director of Project Management for Better Evidence, who helped with the design of the Vaccine Equity Planner. But she noted that schools often represent different stakeholders and may be run by anti-science school administrations. To be engaged in vaccinations, school boards and teachers’ unions may need convincing, she said. Mandates are another issue.

Tucker said that his groups had good relationships with teachers’ union, which by in large support widespread vaccinations; that “evidence-based discussions” and identification of debatable issues can be used in schools, and that “even if a public posture is at odds with what we know to be best, generally educators and most schools have pro-science and pro-evidence members of the community.” In terms of policy, the emphasis should not be on “You should have a mandate,” but rather, “If you want to support a mandate, here are points to make.”

Becky Fox, MSN, RN-BC, of Atrium Health, reiterated the message that schools “are a trusted place of safety” for many and that the school nurse is a figure of trust who can play a role in vaccination education. But she noted that in her area of North Carolina, “we have people who just don’t want the vaccine.”

Tucker acknowledged the obstacles, but said providing resources would help, emphasizing that “there is a probably much larger coalition of the willing who would do something if it weren’t that challenging. Schools have a lot on our plates already. This is the hardest 12 months that any of us have experienced as educators. This next leg of the journey is going to be much more challenging.”

Key Takeaways

- Schools are familiar, public places of safety and trust and school buildings can be ideal sites for vaccination centers.

- Schools can be places for debate on policy concerning vaccinations but can also play a role as a source of reliable, vetted and credible evidence on COVID-19 and vaccines.

- Acknowledging the differences among groups hesitant to get the vaccine is a step in developing the ways and means to reach those different groups.

Bottom up, not top down, will be solution to vaccination efforts in India

July 9, 2021

Members of the renamed Global Vaccination Site Collaborative heard an in-depth, candid report on vaccination efforts in India, a country hard hit in recent months by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Detailing the challenges on July 9, 2021, were Dr. Angela Chaudhuri, a public health specialist and a director and member of the governing body at Swasti Health Catalyst, and Dr. Bhumika Nanda, an expert in health administration and public health. Chaudhuri had just come off a shift in which 973 people were vaccinated in four hours.

While India has suffered great losses from COVID-19, Nanda said health professionals are coming together to look at the complex challenges, find solutions, and deal with vaccine hesitancy. Various vaccination programs are now underway, including mass vaccination campaigns, employers’ programs at factories and corporate offices, and programs for targeted vulnerable populations such as those below the poverty line, transgender people and street vendors. Unfortunately, the most vulnerable seem to be last in line for vaccines.

One of the most significant current challenges is a lack of accessibility to the vaccine. India is relying on the Covaxin, Covishield, and Sputnik V vaccines. Vaccination centers may be far from homes — tribal hamlets are often hard to reach by health workers. Young to middle-aged farmworkers are in the fields during the day and won’t take time off to be vaccinated. Many “cannot afford to lose one day’s pay” to get vaccinated, Nanda said. Registering can be difficult for those without technology.

All this has widened class divisions. Women have been particularly affected, since if there is no male to accompany them to a center or no one to provide child care coverage, they may not be able to get to a vaccination center. Many women lack the autonomy to make decisions about their health; there’s a need to convince the husband to approve it for the wife. Also vaccination centers could have a place for kids to play while parents/guardians get the vaccine.

Indian health professionals are focusing on creating a demand for the vaccine through key messages and addressing misinformation by identifying fears and targeting interventions. “There is a huge mistrust of the vaccine and what it might do; there is not enough information on the possible side effects,” Nanda said. “Misinformation travels at light speed.”

The impact of vaccinating a local tribal leader can be significant. “The feeling is: I don’t trust the government; I trust my local leader. If they tell me to go do it, I will do it,” Chaudhuri explained. In the case of sex workers or transgender people: “I trust my peers because the society hates me.” Also, faith-based leaders can play a huge role in encouraging vaccinations, she said.

“The lead has to be taken by local leadership or people on the ground,” Nanda said.

The two experts described the challenge of updating and sharing information from experience and other sources. “There is a minimum of one new learning a day,” Chaudhuri said.

Collaboration members posed the question: How do we get partners on ground to share their learnings in a collaborative manner? Members suggested setting up a shared document, such as a Google doc, that allows participants to make additions or changes. “Everyone knows this is a source of truth; everyone uses it,” said Eric Goralnick, MD, MS, Associate Faculty, Ariadne Labs and Principal Investigator of the collaborative. Another suggestion came from Margaret Ben-Or, MPH, of Ariadne Labs and a collaboration coordinator: have material posted on a web site that can be copied or downloaded and then updated for a local context.

Despite the tenacity of the Delta variant, there is good news from India. “Most of the cities are beginning to open up,” said Chaudhuri. “We don’t have a hospital shortage anymore. Life is coming back to normal.”

Key Takeaways

- Convenience is key for the hesitant. Minimize travel and wait times, cater to the schedules of daily wage-earners and provide respectful and safe services.

- Use existing trust capital. Reach out to trusted local leaders and community-based organizations.

- It’s not just medical. Utilize non-medical personnel and trained volunteers for community mobilization, crowd control and support, registration, and overall management and troubleshooting.

Incentives and Disincentives for Vaccination

June 25, 2021

The continued urgency for COVID-19 vaccinations was underscored in the June 25, 2021, meeting of the renamed Global Vaccination Site Collaborative, which touched on mitigation efforts in the United States and Brazil. Even as mass vaccination sites wind down, vaccination teams are looking for ways to reach unvaccinated populations — including reluctant health workers.

Matthew McCoy, of Community Organized Relief Efforts (CORE), speaking from Brazil, put the situation in perspective with a report on vaccination efforts there. CORE had helped stage mass vaccination efforts in Dodgers Stadium, and the nonprofit is now partnering with groups in Brazil to create vaccination sites in places like convention centers and samba schools. Brazil has had more than 500,000 COVID-19 related deaths and the local municipal governments are strictly limiting vaccine tiers due to low distribution of vaccines from the federal government, McCoy said. Brazil has experienced low supplies and delays in administering second doses. All record-keeping was previously done on paper; CORE brought in tablets.

Not only is there vaccine hesitancy, but there’s deep distrust of the government — much of it justified, McCoy said, citing examples when saline solutions, not vaccines, have been administered due to corruption. “Most people only want the Pfizer vaccine,” he said. To build trust, people are shown vials of the vaccine and empty syringes to indicate they have received an actual dose. “It’s a lot different from Dodgers Stadium,” McCoy said.

Gill Wright, MD, of the Metro Public Health Department, based in Nashville, Tenn., summarizes vaccination efforts there, including mass sites at Nissan Stadium. About 68 percent of those over 55 in Tennessee have been vaccinated, he said. The state is experiencing a few cases of the Delta virus; overall there is a 1.5 percent positivity rate. More than 60 percent of the homeless population has been vaccinated, but there is a disparity between Black and white vaccination rates. “We are holding events for minorities and the underserved,” he said.

Becky Fox, MSN, RN-BC, of Atrium Health reported on efforts to roll out vaccines to emergency departments and in-patient hospitalization and to increase vaccination rates to 75 percent by July 4 to “teammates” in health care. Fox admitted concern that this rate is not higher. Teammates’ reasons for not getting vaccinated include the inability to access vaccines, coordination with work schedules, insufficient education on vaccine safety, and a “wait and see” approach. Some remote workers say that since they don’t go into work, they don’t need the vaccine. Fox added, “I wish I could say ‘Look at Brazil.’”

This led to a discussion of vaccine incentives — and just as important — disincentives. Fox cited vaccine lotteries and scholarships giveaways as well as getting rid of policies that pay people to stay home if they suspect they have been infected. However, mandating vaccination for all current employees may not work; “You can’t fire 25 percent of your workforce,” noted Dan Resnick-Ault, MD, of the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Said Fox, “We all need to do this together.”

She added, “We have to remind ourselves as long as we’re moving in the right direction, we’re doing OK.”

Resnick-Ault gave a rundown of efforts in Colorado, including the winding down of the mass vaccination site at Coors Stadium and a shift to providing vaccines through emergency departments; this could extend to patients’ family and visitors. However, so far, only 517 doses have been given in emergency departments, which generally see 280 to 360 patients a day, he said.

Resnick-Ault noted the difficulty of holding conversations with hesitant patients in the emergency department when physicians are already busy. Yet the ED encounter represents the first non-social and non-media source of information on vaccines for many patients. “We will bend over backwards to get people vaccinated,” he said.

The slowdown in vaccination rates concerns members of the collaborative although they acknowledge this was perhaps inevitable. Observed William Roy, Federal Coordinating Officer with FEMA region 1, “We knew we were going to hit the wall. There definitely needs to be a carrot-and-stick approach going forward.”

Key Takeaways

Both incentives and disincentives can be used to increase vaccination among health workers.

- Incentives include: Awards or prizes; relaxing mask-wearing policies; sponsored meals.

- Disincentives include: Elimination of paid absent time for suspect COVID exposure; limiting participating in activities like conferences and travel.

- Mandate all new hires to be vaccinated.

To encourage vaccination for the general public:

- Offer vaccine during health screenings.

- Increase vaccine availability at on-site clinics.

- Establish “Vaccine to You Rounding Team” to bring vaccine units in key areas to acute care facilities.

- Support rounding teams with vaccine ambassadors and/or infectious disease experts.

- Push “safety for patients” message.

- Share internal data of vaccine effectiveness.

Shifts in Vaccination Focus: International and Children

June 4, 2021

Even as mass vaccination sites are winding down, members of the Global Mass Vaccination Site Collaborative see new challenges looming. One is how to engage colleagues globally who are considering mass vaccination sites as part of their vaccination strategy, and another is the issue of vaccinations for children under 12 years old.

“We know that the risk of infection for this age group is low, but we are still not sure about long-term immunity and whether children can be vectors for COVID-19 infection,” noted Eric Goralnick, MD, MS, Associate Faculty, Ariadne Labs and Principal Investigator of the collaborative, during the June 4 meeting.

Jonathan Ballard, MD, MPH, MPhil, FACPM, of the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, shared his concerns about the ability and willingness of private providers nationally to offer vaccinations in their practices given the constraints with storage and handling, documentation, and multi-dose vials. He expressed uncertainty about whether pharmacies will administer vaccines to children as young as two years of age when vaccines are traditionally administered in pediatric offices for this population. His main worry is if there will be enough vaccine providers for younger children, and there may be a need to restart publicly administered vaccinations again in the fall such as children-friendly vaccine sites.

Other discussion points centered on possibly using schools as vaccination sites, the difficulty of getting consent forms filled out — either online or on paper — and what may happen with booster shots.

Amy Young, MD, of the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin commented that there have been some post-vaccine positive cases, mostly with the Alpha variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom. The consensus of the group was that much is yet to be learned about variants. “That’s the big, black box,” Dr. Goralnick said.

Also discussed was vaccination efforts in India and Brazil and how to incorporate vaccination into primary health care.

Key Takeaways

- Be cautious about shutting down mass vaccination sites if there is a chance they will need to be re-opened in the fall. Considering building plans on how to quickly and efficiently re-open sites if needed.

- International efforts should consider how to relieve fatigued and stressed health-care workers as well as getting shots in arms.

- Consent forms for getting children vaccinated will be a challenge. Plan ahead as much as possible.

Assessing Risk on a Plane — As You Fly It

May 21, 2021

The question was put to the Zoom audience of team members who run mass vaccination sites: Did you proactively do a risk assessment ahead of time to ensure safety and reliability?

Pause. Then Becky Fox, MSN, RN-BC, of Atrium Health, said, “No. We had six days to get ready, and one of those days was a holiday.”

Others nodded. Said Captain Dirk A. Warren, M.D., the Surgeon General of Joint Task Force Civil Support, “We were building the plane in flight.”

But this was exactly the point of Karen Fiumara, Executive Director of Patient Safety at

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who did a presentation on risk management for the collaborative on May 21. Health managers have to focus on both system reliability and human reliability, she said. Distraction, experience, and implicit bias are all part of that human performance. “We consider a system effective if the system manages a risk,” she said. However, “resiliency does not mean unbreakable.”

In a lively back-and-forth exchange, members of the group spoke honestly about the challenges of setting up a system “in flight” and the inevitable incidents that occurred along the way. These included unprepped syringes and unforeseen environmental problems, such as an elderly person who failed to negotiate an escalator.

“If you think you did have a perfect scenario, you probably don’t realize your errors,” said Eric Goralnick, MD, MS, Associate Faculty, Ariadne Labs and Principal Investigator of the collaborative.

Others were positive. Said Will Roy, Federal Coordinating officer with FEMA region 1, in the Zoom chat: “From my personal experience in visiting VAX sites the feedback from the guests has been nothing but positive — ‘flowed like a well-oiled machine’ was the majority of the comments.”

“We scaled up as we learned along the way,” said Randy Van Straten of Bellin Health. “We also learned to partner better with community assets.”

Fiumara stressed that the “cultural experiment” of the pandemic could be used to improve safety in health systems. Her points included:

- Examine errors. Is it the person or the system? Most of the time it’s the system.

- There are two reasons why humans follow rules. One: You’re afraid you are going to get caught if you do not follow rules. (You drive differently when a police car is behind you.) Two: You appreciate the risk of not following the rules.

- You cannot punish somebody into better task performance.

- Avoid attributing vaccine hesitancy to specific groups. Rather, emphasize that there is a “well-earned distrust of the medical community.” Roy noted that you can really only say there is hesitation when you have the supply and the opportunity for vaccination, which was not the case. “We shot ourselves in the foot right out of the gate,” he said.

- Humans are only vigilant to a certain level for a certain period of time. People have to be acutely attuned to risk to remain aware of it.

Fear? Football? Free drinks? Freebies? What Motivates People to Get Vaccinated

May 14, 2021

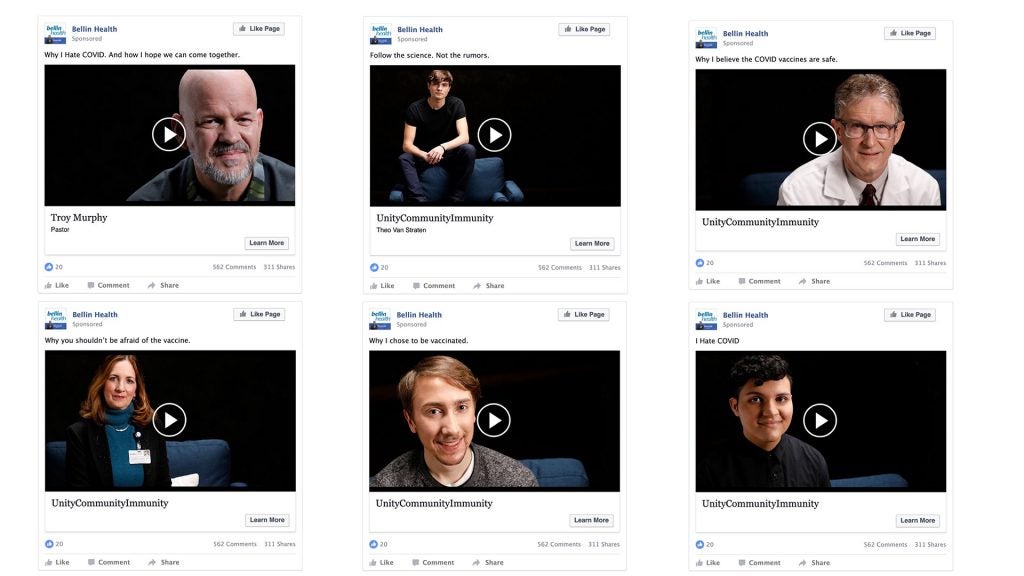

What encourages people to get vaccinated? In the case of Green Bay, Wisconsin, it may have been the chance to look over Lambeau Field — the home of the Green Bay Packers — from the elite seats. During the May 14 collaborative meeting that focused on creative ways to get shots in arms, Randy Van Straten and Andrea Werner of Bellin Health presented on the mass vaccination efforts by Green Bay Public Health, the Green Bay Packers organization, and Bellin Health. The Lambeau Field site opened March 16 and about 38,700 people have been vaccinated there, an average of 1,200 people per day.

A vaccination site was first staged in Lambeau’s atrium, then moved to the eight terrace suites that overlook the playing field. Van Straten said the numbers of those seeking vaccinations has spiked, helped by the live media feeds from the suites. “The terrace suites are not an area (the average fan) can get into, and by opening this up we are seeing an upswing,” he said.

There may also be an impact from the effective marketing and outreach strategy the health partners have conducted with the 9Rooftops Marketing Agency. Werner described a campaign utilizing local and community influencers rather than actors. Called “Unity.Community.Immunity,” the campaign aims to reach the Latino, Black, Somali, and Hmong communities of Green Bay. “I don’t like the word ‘hesitancy,’” Werner said. Instead the partners have chosen to focus on the structures that hold people back from getting vaccinated. A media campaign with videos featuring the slogan “I Hate COVID” also seems to be having an impact.

Van Straten stressed how the collaborative’s May 7 meeting on “guest experience” was applied to the Green Bay efforts. “You took it from Friday and implemented on Monday,” noted Eric Goralnick, Medical Director of Emergency Preparedness, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Ariadne Labs associate faculty who is helping to lead the collaborative.

Van Straten and Werner spoke of challenges. Their team has staged about a dozen mobile sites with 600–700 vaccinations each; however, when Van Straten reached out to meat-packing plants for onsite vaccination, of 1,800 surveyed, only 9 responded positively. The team planned to administer a total of 1,200 shots in a Navy shipyard, but only did 300 vaccines in a two-day period. The group acknowledged that a sense of urgency might have decreased.

The group discussed different creative efforts to encourage vaccination, citing a New York Times article and a MIT study. In North Carolina, breweries offered a free beer if you get a shot. The effort has been effective but there has been backlash from a similar effort in Wisconsin by those who say it encourages drinking.

Could coupons for shots work as well? Could vaccines be ordered like pizza delivery? “How can we figure out how to meet people where they are,” said Van Straten.

Key Takeaways

- Incentives for vaccinations can take many forms, from offering shots in an alluring place (like Lambeau Field’s top-level suites) to handing out a free beer from a site in a brew pub.

- Media campaigns can be most effective when they employ local influencers, rather than actors.

- A hub and spoke model for vaccine distribution, in which a central location then supplies mobile or satellite clinics, can be effective.

- People may be losing a sense of urgency about vaccination but vaccination efforts should not be deterred, rather teams should settle in for a long haul.

Be Our Guest: Turning Vaccination into an Experience

May 7, 2021

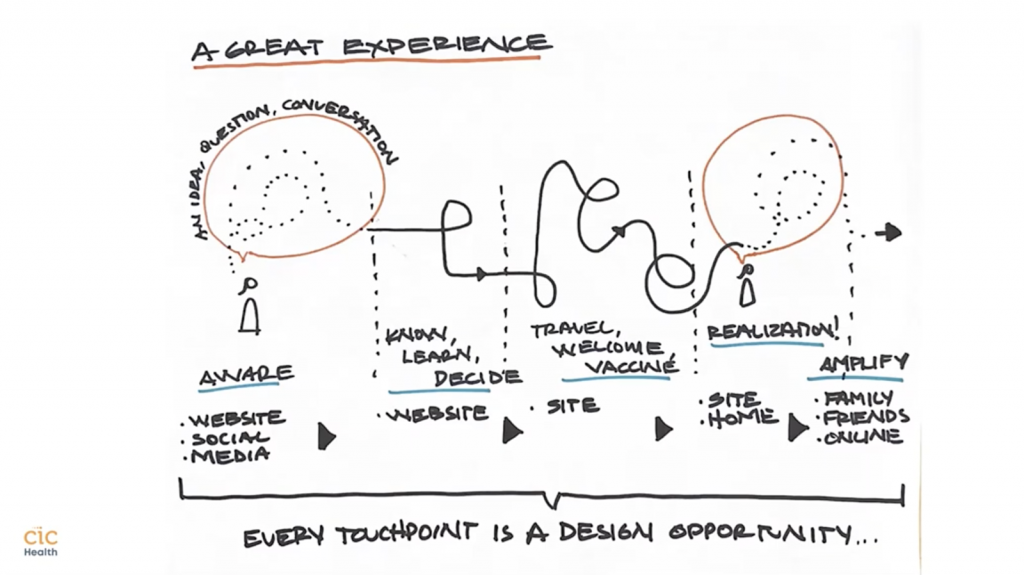

What to call the people getting vaccinations at a public site? The word is “guest,” according toCIC Health Matt West, director of operations, and Rodrigo Martinez, chief marketing and experience officer. They presented on May 7 on how they ran three mass vaccination sites and about 19 pop-up sites in Massachusetts. “From the beginning we’ve called them ‘guests,’ not ‘patients.’ They are not sick, they are our guests. That gets the staff to act more as a host,” Martinez said.

The use of the word “guests” underscored the key point of the presentation: “Overall, the experience of the vaccine is as important as the vaccine itself.”

CIC Health runs four mass sites — Gillette Stadium in Foxboro, Fenway Park in Boston (now closed), the Reggie Lewis Track and Athletic Center in Roxbury, and Hynes Convention Center in Boston. The Hynes is also the hub site for outreach to five cities: Boston, Chelsea, Revere, Fall River, and New Bedford. West shared considerations for this “hub and spoke” model, such as:

- Setting up pop-up sites on Revere Beach, a popular location for the area.

- Working with cities to set up special vaccine buses that would move from bus stop to bus stop to administer doses.

- Use pop-up sites like churches, high school stadiums, and community centers during some days of the week for first doses, while maintaining a fixed site for second doses.

“We are trying to be as creative as we can be,” West said.

Martinez emphasized the use of human-centered design when creating the overall guest experience, beginning when guests visit the CIC Health website and ending on social media. The first sign that people should see at a site is a “Welcome” sign that recognizes the importance of the moment, he said. After their vaccination, guests may be given space for taking selfies to post their story. For example, sites can allow someone to record responses like “I dedicate my vaccination to my grandmother,” collect the various responses, and spread them through social media. “We create a stage for them to tell their story,” he said.

Key Takeaways

- Vaccination is not merely a procedure. The experience of the vaccine is as important as the vaccine itself.

- A communication strategy should be set at the beginning of the operation and refined throughout.

- Vaccination sites should utilize design principles and consider human factors, such as how you welcome people, set expectations, and provide information.

- Strive to amplify the effect of vaccination by creating social media platforms.

- Aim to turn every guest into an advocate for vaccination.

- Highlight and create assets out of milestones; share and allow guests to share these assets.

The Rules of Engagement for U.S. Military in Emergencies or Medical Crises

April 30, 2021

How do U.S. military personnel — soldiers, sailors, and others — end up in a community to help out with situations like mass vaccinations? The April 30 virtual meeting answered this question by focusing on the deliberate process and operating principles used by the military to determine when and how to deploy personnel in state or local emergencies. Presenting were Major General Jeffrey P. “Jeff” Van, Commander, Joint Task Force Civil Support, Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Virginia and Captain Dirk A. Warren, M.D., the Surgeon General of Joint Task Force Civil Support. Dr. Warren outlined the overview of how the Department of Defense provides Defense Support to Civil Authorities:

- The President or the Secretary of Defense must authorize the support.

- It mitigates the effects of a disaster or catastrophe (manmade, natural, or terrorist).

- It provides temporary essential services at home or abroad.

- Department of Defense always operates in support of the Lead Federal Agency.

The chain of command may appear complicated; however, the goal is to ensure coordination between the Department of Defense and local, state and federal authorities.

When asked about the timeframe of response, Dr. Warren said it is usually about a week but can be expedited, particularly with commanders who have immediate response authority and can take immediate action if they believe they can save lives or mitigate property loss after a disaster has been declared. Commander Van noted that “we can move within hours” if a need is anticipated.

Key Takeaways

- The U.S. Military is prepared and ready to lend aid. The Department of Defense follows set protocols to ensure that military personnel always coordinate with civilian authorities.

Coping With an Ever-Changing Vaccine Landscape

April 23, 2021

The ever-evolving status of COVID-19 vaccines — including the sudden pause on use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine — preoccupied attendees of the April 23, 2021, collaborative meeting. Eric Goralnick, MD, MS, Associate Faculty, Ariadne Labs and Principal Investigator of the collaborative lead a round robin discussion in which members shared current challenges.

Discussion was centered on inventory, second-dose appointments, and on how to transition from mass sites to smaller or mobile sites. In Massachusetts, 75 percent of residents are projected to be vaccinated which may lead to closing of large vaccination sites. Collaboration members were also seeing slowdowns in smaller mobile sites as well as mass vaccination sites. Could this be due to hesitation or mass saturation? There were no clear answers.

Becky Fox, MSN, RN-BC, of Atrium Health acknowledged no-show rates have increased in certain efforts from 2% to 8%, which led teams to look for other creative initiatives to bring vaccines to the patients. It was an exercise she compared to “a bit of throwing vaccine-spaghetti against the wall” to see what sticks. The team is shifting to smaller, mobile units but wants to continue to have a mass site presence, so that if and when the need arises (e.g., mandatory requirements and/or school requirements), Atrium Health could expand quickly. Examples include small church groups, behavioral health outpatient treatment centers, restaurants, and small businesses where the number of vaccines ranged from 5–40 total doses per event.

Fox raised another issue: required vaccinations for health-care workers.” If we (health systems and clinical experts) agree vaccines are important, how do we push OUR health care systems to say, ‘This is mandatory for all of our employees?” The issue of requiring college students to get vaccinated was raised with reference to this article and this one. Other organizations shared that they too are considering mandates but would prefer to implement once full FDA approval for the vaccines is received.

Collaborators discussed how to juggle vaccines that must be kept frozen with no-shows. Maintaining inventory remains a crucial issue — everyone is determined that every shot be used. Instead of giving fully thawed Pfizer vaccines, Adrian Backus of CORE described using mobile freezers and thaw as needed. At the time Pfizer had recently released guidance allowing for 14 days of storage in a freezer.” (This has since been updated. See here.) “When you get to the end of 14 days in the freezer, you have an additional 5 days, so you have 19 days,” Will Ford of UC San Diego Health, noted. “You can dilute and draw to give yourself another 6 hours according to Pfizer.” Another issue was whether to offer two different vaccines — like Moderna and Johnson & Johnson — at the same place and offer the choice to people.

Fox described a “great” event in Charlotte in which a vaccination clinic was held at a brewery and those getting shots got a free pint (provided by the brewery). Staffed with about 5 to 6 people, the event drew a diverse group of 107 people aged 18 to 35. No appointments were needed, and it was held in the evening, as many patients have described the challenge of getting to a vaccination site during daytime hours due to their work schedules. There were zero reactions or complaints of anxiety or nervousness — “that was the coolest part, as the observation was in a beautiful outdoor space, where patients could enjoy their beverage if they wished, while they waited.” Social media was used to promote the event, giving it a “cool factor.” They plan to go back to the brewery in three weeks for second doses. This was a good example of “going to the people,” said Margaret Ben-Or, Ariadne Labs’ project manager for the collaborative.

Key Takeaways

- Stay flexible.Vaccination efforts may morph from mass sites to smaller sites, but a hybrid model might work at the current time.

- Be clear about guidelines for thawing vaccines as teams may have more doses than they first realize.

- Be creative. Go to where people are — even if it is a bar.

Dream Helps Solve Potential Nightmare

April 16, 2021

Data collection and logistics was the focus of the virtual April 16 meeting. Dan Resnick-Ault, MD, administration and operations fellow for the Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, presented on the challenge of creating a mass vaccination site at Coors Field in Denver. He began his talk by noting that military data indicates that if you could create a good “throughput” or traffic flow with less queuing, you can run a site for fewer hours, decrease staffing costs, and increase the vaccination rate. Thus, his team’s goal was creating an effective traffic flow.

The vaccination site at Coors Field opened February 2021 and was soon able to administer 5,000 doses during a 6-hour window with 200 staff. Two traffic lanes were set up to feed into six queuing lanes that led to the registration tents. Bail-out or snafu spaces were set up to pull aside those cars with problems with registration so as not to block the flow. Cars successfully registered were then sent to 16 vaccination tents and finally directed to observation parking lots. A command post was set up on top of a nearby four-story parking lot. Data collected indicated that 830 cars were processed in an hour.

Resnick-Ault described some of the issues encountered. For example, lanes leading cars to the observation lots narrowed to two lanes and caused a backup so severe “we actually had to pause vaccination at one point,” said Resnick-Ault. Michael Skaggs, a first-year medical student, had a dream about a better way to do this workflow. Before medical school, Skaggs ran a whitewater rafting company in which he had to juggle through-put and timing for a fleet of rafts. Translating that operational skill to the vaccination site, he envisioned having vehicles distributed in a serpentine manner to the observation parking lots and then discharged out to the side. “This means the ingress lane to the traffic is never paused.”

The Colorado team found that the first weekend, people spent about 22.48 minutes total on the site. One of the slow-down points was in registering patients. The team eliminated a separate registration step by registering people at the point of vaccine delivery. With the addition of a mobile app for registration, the team was able to reduce the median time from registration to vaccination from 4.27 to 2.18 minutes, thus decreasing overall time.

Other challenges involved frigid temperatures that made it difficult for staff to operate outside. This was solved with the use of a “mega tent” wide enough for eight lanes. Additional snafu spaces were added to ensure traffic continued to flow smoothly.

The group discussed the issue of holding people for observation in case of a severe allergic reaction. Liquid Benadryl was kept on hand and given to those who said they didn’t feel well. Resnick-Ault recalled a lesson from the Cardinals mass vaccination site in Arizona from which his team learned and incorporated into their setup. In Arizona, a row of ambulances was first stationed near the observation lots; they were later moved out of the direct line of sight, Resnick-Ault said. “When people could see a row of ambulances, they had lots of reactions. When [the ambulances] were moved behind, all their problems went away.” In Denver, people were not pressured to leave lots; no severe reactions requiring hospitalization were observed.

While the Coors site was closed due to a lack of vaccine supplies, Resnick-Ault anticipated that the lessons learned could be applied if re-opened. “We think we can do 15,000 a day without breaking a sweat,” he said.

Key Takeaways

- The use of a “bail-out” or snafu space for drivers with registration issues to pull into is crucial to keep the general traffic flowing.

- When the team began to use Epic Rover, a mobile app that allows clinicians to record documentation and conduct barcode validation at the point of care, they were able to substantially reduce the time from registration to vaccination.

- The creation and implementation of a real-time data collection tool allowed for visualization of throughput and actionable data for day-of and post-hoc clinic improvements.

- The reduction or elimination of post-vaccine observation time for a second dose might be considered, although this was not a point of universal agreement.

Charlotte Motor Speedway and Bank of America Stadium: >36,000 vaccines in less than 10 days

April 9, 2021

How many 75-year-olds get a chance to drive on the Charlotte Motor Speedway? That was one of the draws for a mass vaccination site set up by Atrium Health, a health system serving patients at 42 hospitals and more than 1,500 care locations in the South, when the system pivoted to provide COVID-19 vaccinations in winter of 2021.

The goal was 1 million vaccinations by July 1, explained Becky Fox, MSN, RN-BC, of Atrium Health, during a presentation on April 9, 2021, to the collaborative. Fox’s presentation covered the team’s efforts to get a mass vaccination process set up, from the planning to the adjustments along the way. One of the initial drive-through sites was the Speedway because, as the staff joked, “No one knows how to move cars faster than a speedway.”

With less than a week to prepare, Atrium launched its vaccination efforts in partnership with Bank of America, Honeywell, and Charlotte Motor Speedway. They provided not one but two large mass vaccination events, including the first in North Carolina. The team used innovative creations that allowed patients to be processed in less than 45 mins, with a 22–25 min average. For example, a screening app sent via text message to patients prior to their appointment identified the patient and screened them for 15 or 30 minute wait times. Multi-field barcodes sped up the medication documentation and required state registry documentation processes. The medication process requires 9 different fields to be documented, which is cumbersome when processing 500–1000 patients per hour, Fox shared. Instead, the 60-second process was brought down to two seconds. “A reporter called us the world’s largest pit crew,” Fox said.

Some challenges emerged from the patient population and sites. “A lot of patients came in with what I called the ‘vaccine fog,’” Fox said. “These were patients who were emotionally overwhelmed by the pandemic, the vaccination efforts and had trouble focusing, so we had to really ensure our communications, our signs, and our processes were smooth, as we were committed to also delivering an outstanding experience.” With a different format of both a walk-in and drive-through site at the Bank of America Stadium, less than five days after the first event, this posed additional difficulties. Because parking was some distance from the vaccination site, staffers provided personal concierge service to those who needed it via wheelchairs; one staffer racked up 37,000 steps in a day taking patients from their car, through the experience, and then returning the 0.2 miles back to the parking garage.

Burnout and trauma for staffers — who had already been dealing with COVID-19 for months — was a prime concern. The “Fill Your Tank” Program was developed for the mass vaccination events, asking front-line staff to work in the vaccination lines, where hundreds of times a day, they heard, felt and saw gratitude from patients and the community. “We wanted to make it a great experience for the team AND the patient,” Fox explained, “and we heard over and over again from staff, how this was some of the most meaningful work they felt they had ever done, and truly the best of Atrium Health and humanity shining through.”

The mass vaccination events and lessons learned were spread to other events held in the community at surrounding counties and included other sites such as colleges, universities, and at the airport in partnership with American Airlines.

The team was confronted with the question of: How do we get vaccinations to people at home without transportation? The decision was made to send small groups of nursing staff to pods of housing locations. No-shows were a problem. During spring break, 4,500 people signed up but only 4,000 showed up.

Key takeaways

- Utilize healthcare staff, especially nurses, to lead the efforts.

- Think like Disney and “prime the line” so that people get through quickly with the goal of making it a pleasant experience.

- Keep track of data and use it to make real-time adjustments. For example, if you find you are running no-show rates of 2–3 percent, schedule more appointments using social media to alert people.

- Manage private-public partnerships for effective results.

- Set up processes and policies so doses can be taken off-site to manage the left-overs, i.e., establish a chain of custody.

- People feel more comfortable going somewhere in the community rather than being shuttled to another location.

CORE tackles vaccinations from mass sites to mobile units

April 2, 2021

The switch at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles from a testing site to a vaccination center was a truly daunting effort. Marlina Crespo, the COVID-19 area manager for the Community Organized Relief Effort (CORE) vaccination effort in Los Angeles, acknowledged this during the April 2, 2021, meeting of the Collaborative. “The amount of equipment and human resources required was definitely not something that we were expecting. We underestimated the scale,” she said.

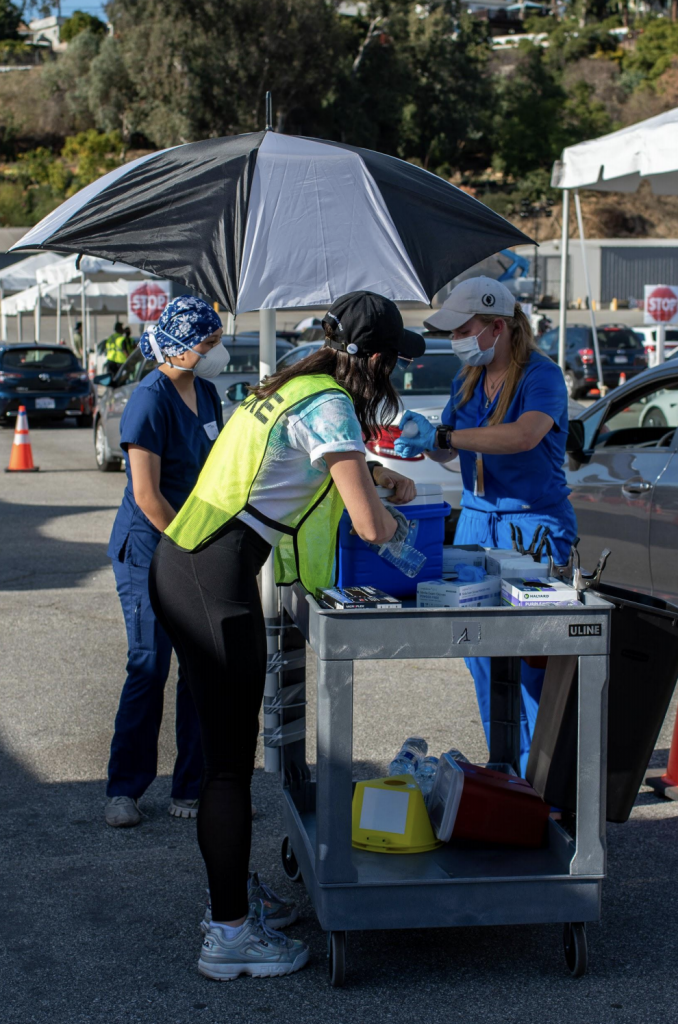

Nevertheless, more than a million vaccines have been administered in the City of Los Angeles, and nearly 480,000 vaccines were administered at Dodger Stadium — about 12,000 to 15,000 a day — by a staff of about 480 between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. Crespo, with CORE Co-founder and CEO Ann Lee, explained how their team approached the massive vaccination effort.

Their challenges included:

- Ensuring sufficient supplies across such a large, spread-out venue.

- Having all staffers HIPAA certified.

- Oversight in such a large, spread-out venue.

- Traffic impact in the neighborhood.

- Ensuring enough vaccines were on hand but not overdrawing and risking the vaccines expiring.

- Maintaining communications among the many partners, which included the mayor’s office, the local fire department, medical software companies, local universities, and community organizations.

The team was able to come up with innovative operational solutions, including having a vaccine cart that went from car to car; color-coded vests to distinguish functions among staff; a tracking system created by medical students to track which vaccines should be used first; and yellow magnets placed on cars to indicate observation time needed. Initially, it took as long as 4 hours for a person to receive a vaccination; currently, time can range from 2 hours to less than 30 minutes depending on the crush of the crowd. “Everything needs to work together to be functional,” Crespo said.

CORE also runs mobile units giving 4,000 doses a day; a drive-up and park unit giving 5,000 daily; a walk-in unit at 3,000 a day; and a mobile unit that reaches out to people experiencing homelessness. CORE also works with Access LA, which provides transportation for people without other options.

Lee noted the most efficient and cost-effective model is the walk-in clinic; running mass sites, such as that at Dodger Stadium, can be extremely costly, although insurance reimbursement seemed to be covering most of the costs.

Lee also spoke highly of the effectiveness of mobile clinics, which were sent to an area for a week or so. People did not need appointments, and the word that a unit was there spread quickly in a neighborhood. Mobile clinics have administered over 73,000 doses, 90% of them to people of color. The team also hoped to send a vaccination unit to a garment factory to reach undocumented workers.

“Having so many different options is important,” Lee said. She expects an emphasis on the mass vaccination sites in next months and then a focus on walk-up sites and mobile units later in the vaccination campaign.

Key Takeaways

- Be prepared for unexpected difficulties.

- Mobile units are helpful for reaching those without access to computers or wifi or with limited computer skills.

- Walk-in clinics may prove to be the most cost-effective option.

Kickoff Meeting Delves into Logistics of Nashville Event that Vaccinated 10,000 in a day

March 26, 2021

As the vaccination efforts were gaining steam around the world, the collaborative held its kickoff meeting to begin the weekly effort to share information, best practices, and stories from the vaccination frontlines.

The March 26 meeting featured a presentation by Rachel Franklin, MBA, AEMT, of the Metro Public Health Department in Nashville, Tenn., who described the mass vaccination effort at Nissan Stadium in Nashville. In one day on March 20, over 10,000 people were vaccinated — an impressive effort that also provided key insights into how to stage such large events.

Organizers drew on previous plans, infrastructure, and funds for other kinds of medical emergencies, underscoring the message of always being prepared. Tennessee got 100,000 doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine and asked local health organizations to administer quickly. “We had 18 days to do this,” Franklin explained.

While organizers had a ready site at the football stadium, nothing had ever been done at such a large scale, Franklin said. She described the logistics — creating 20 lanes of traffic, putting together vaccine kits on site, creating the registration process, and using green cards indicating a person was good to go for a vaccine. The team had to be efficient. “It’s hard for nurses not to be conversational but we had to keep it moving,” Franklin said. When a central location used for putting together vaccine kits could not keep up with flow, the team pivoted to create a way to put together kits at each lane. They used pre-printed stickers so that reduced time on writing.