By Stephanie Schorow for the Global Mass Vaccination Site Collaborative

One of the strengths of the Global Mass Vaccination Site Collaborative has been the presentations by organizations and individuals from all over the world about their approaches to setting up and running COVID-19 vaccination sites. On Nov. 19 and Dec. 17, 2021, VillageReach, whose mission is to transform health care delivery to reach everyone, shared insights from its vaccination work in places as varied as Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Seattle, Washington.

While the challenges of launching and running vaccination sites differ markedly among locations, some commonalities emerged, such as the need to stay nimble and flexible, to form partnerships, to create hyper-localized responses, and to present vaccination as an opportunity for the public, not a mandated burden.

“Our approach is additive. We bring together the needs of the health system with the needs of those who receive services,” Julia Guerette, Data Analytics Manager of VillageReach, told the collaborative during the Nov. 17 presentation.

VillageReach has offices in Seattle, Washington, Mozambique, Malawi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo and has partners in Liberia, Tanzania, and Cote D’Ivoire. On Dec. 17, the presenters were Vidya Sampath, VillageReach, Director & Global Team Lead, Data Analytics; Freddy Nkosi, VillageReach DRC Country Director; Carla Toko, VillageReach DRC, Advocacy & Communications Manager; and Hyacinthe Mushumbamwiza, the Rwanda Country Representative of the Clinton Health Access Initiative.

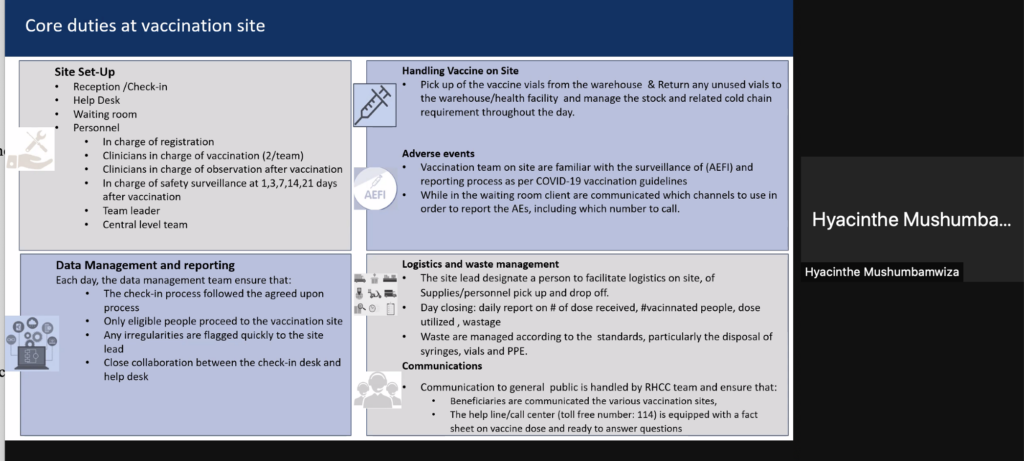

A mass vaccination site had been launched just a few weeks previously in Kinshasa, DCR, with the goal of vaccinating 1,000 people a day with a seven-day-a-week, in an 11-hour-a-day operation.

“We had to create something within the limitations of the physical space provided by the government; it took about six days to set it all up,” said Toko. Clients were given juice and water when they arrived and comfortable couches were provided for observation periods. The site’s setup, both operationally and physically, had to be nimble enough to respond to unforeseen challenges – for instance, within two days of sit opening, the roof of the center’s tent was damaged by a severe rainstorm, forcing a temporary halt, but the site was running again within a day. As of Dec. 17th, 2,237 shots had been administered.

This may not seem like a lot, noted Nkosi, but in the context of a city like Kinshasa which has had a slow vaccination uptake, it was significant – the site is currently responsible for 50% of the vaccinations taking place in the health area where it is situated, while 15 health centers are also providing vaccines. However, more vaccine delivery modalities are needed. “Some people won’t go to a site; we have to go to the people so we are organizing a mobile strategy,” Nkosi said.

About 80 percent of the shots given so far have been to males. “Many women are very concerned about fertility” or the vaccine’s perceived effect on pregnancy and breastfeeding, Nkosi said. “That explains the difference between men and women. But an effort is being made to correct the misinformation on social media.” As in the United States, African countries are coping with misinformation and myths spread by social media; some people still deny the existence of COVID-19.

Vaccination efforts by VillageReach include development of an implementation plan guidebook, dissemination of tools, templates and best practices, and sharing material through white papers, journal articles, videos and podcasts. Vidya Sampath, who polled other collaboration members during the Dec. 17 meeting, said evidence “shows a real community” of vaccine site operators who want to learn from another. “We can have a real peer group and community working on this together,” she said.

While the majority of VillageReach’s work is focused on Africa, public health officials in Washington State reached out to VillageReach last year to help with the vaccine rollout, given their expertise in vaccine supply chain logistics and distribution.

In close collaboration with multiple local health jurisdictions around the state, VillageReach held listening sessions with community members and produced infographics. Guerette worked on data visualization – down to the zip code level – to aid in the development of equity driven outreach efforts. VillageReach was also able to plug into resource-strapped local health systems with assistance on minor tasks, such as setting up a Google survey. “No task is too big or too small” for support, she told collaboration members.

Public/private partnerships can help depoliticize the public health system, Guerette said. “With COVID, public health (in the U.S.) has become very political, whether you like it or not,” she said. “We find that partnerships can break down those [barriers].”

In rural, mostly white counties in Washington, VillageReach emphasized “listening” efforts. “COVID is the first time [many residents] have had to interact with the public health system,” Guerette said. VillageReach was seen as “neutral,” which proved to be an advantage in the politicized atmosphere.

“Who would have thought that a global health organization would be the people to talk to folks in rural Washington – but it has ended up working pretty well,” Guerette said.

Key Takeaways:

- When providing COVID-19 related support, try to do so in a way that strengthens the local public health system as a whole.

- Engage the government as stakeholders, get buy-in from local jurisdictions.

- Be ready to change strategies. After the first few days of a vaccination site’s operation, evaluate the operation open hours.

- Don’t expect the community to just “come to you” without extensive outreach work.

- Community health workers can be effective in encouraging people to get vaccinated.

- Be sensitive about local politics: “Even those who get vaccinated may not want others to know that they are vaccinated, ” Guerette said.

- Be encouraging. Signs in Kinshasa say proudly in French: “I have been vaccinated against COVID-19 via the Vaccinodrome. How about you?”

- Health workers everywhere are swamped, burnt out and discouraged. Think outside the box for ways to alleviate the burden, even with small tasks.

The Global Mass Vaccination Collaborative was launched in April, 2021 as a way for stakeholders directing vaccination campaigns around the world to come together and learn from each other’s efforts. This blog series was launched to record and share the learning and insights gained from this collaboration. Read blogs from our previous meetings here.