How do you solve a problem like loneliness from a public health perspective? The students participating in an Ariadne Labs-sponsored, human-centered design workshop pondered that question. Research shows that loneliness is as bad for our health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day. But what can we do about it?

Participants in the Feb. 24th workshop held at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health came up with a myriad of possible solutions. Their brainstorming was the culmination of an interactive workshop that gave students a taste of how human-centered design works and a glimpse into how Ariadne Labs fulfills its mission to save lives and reduce suffering everywhere by creating scalable, systems-level solutions.

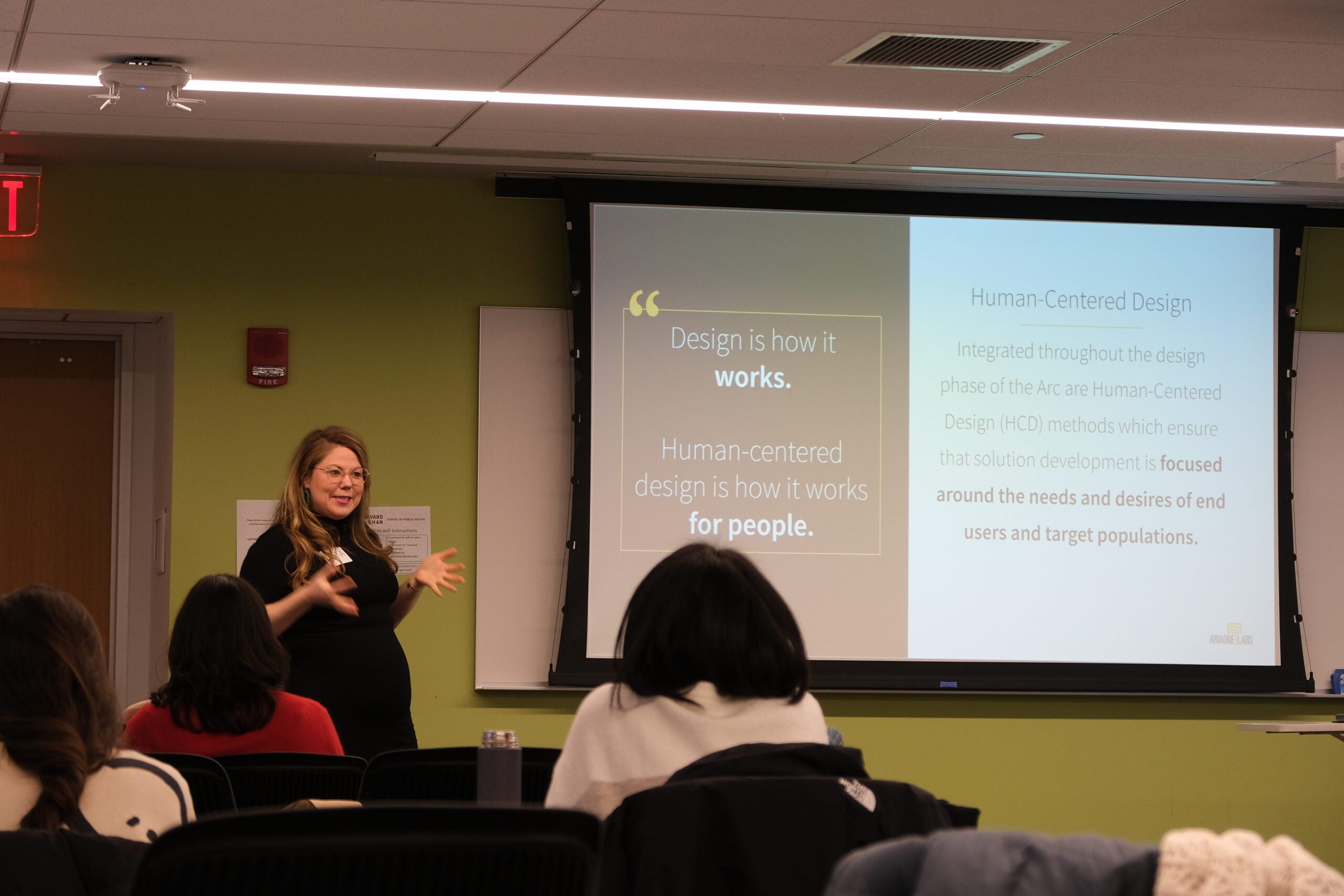

The workshop, run by Meghan Long, Assistant Director of Ariadne Labs’ Innovation Platform, and Laura Onelio, Design and Innovation Specialist, walked students through a multi-step process to show how the principles of human-centered design can be used to create innovative solutions to pressing public health problems.

What is Human-Centered Design?

Human-centered design is often defined as a process that focuses on the needs and desires of end users and target populations. People’s voices “are the heart of human-centered design,” Long said. Ariadne Labs uses human-centered design both as an overarching approach to the labs’ projects and as a standardized methodology. Specifically, Ariadne applies this process to finding solutions for issues in public health and health care delivery.

To ensure that solutions meet the highest standards of science, the lab applies its innovation pathway, the Ariadne Labs Arc, a process of Design, Test, and Spread. Human-centered design is integrated throughout the design phase of the Arc to ensure that solution development is focused around the needs and desires of end users and target populations.

“What we value at Ariadne is that all of our solutions are patient-centered,” Long said. “To be able to do that, we use methods like human-centered design to ensure that users are at the forefront of our solutions.”

Ariadne’s process for human-centered design follows a few general steps:

- Understanding the problem and context: Ariadne researchers speak with key stakeholders, conduct literature reviews, and map current and ideal systems to understand the context within which a problem occurs. They engage people who would ultimately be using the solution to validate the problem and gather inspiration through empathy interviews, user profiles, and stakeholder convenings.

- Ideation and prototype creation: This information is used to brainstorm potential solutions and create an initial prototype for early testing.

- Testing and iteration: The prototype is iterated on and tested with stakeholders or in real-world settings, and researchers solicit feedback to refine and improve the prototype.

- Implementation and continued feedback: The lab develops an implementation strategy with supporting material to spread the solution across health systems, while continuing to iterate for improvement.

During the workshop, Long and Onelio showed how the human-centered design process works in practice, highlighting the development of TeamBirth by Ariadne’s Delivery Decisions Initiative. Researchers initially approached the issue of how to improve patient experience during labor and delivery and to safely decrease cesarean birth rates. They focused on how to support the people involved in labor and delivery including the person giving birth, family members, providers, and support people such as midwives and doulas. Two core tools were developed: a shared planning white board displayed in Labor and Delivery rooms and team huddles that bring the patient, family, and care team together around this board to discuss progress, preferences, and next steps. These solutions were developed in an iterative process that incorporated feedback from families, nurses, physicians, and other stakeholders.

TeamBirth has been proven to improve teamwork and communication during labor and delivery, and it’s now been implemented in nearly 60 health facilities across the country.

Applying the Method: Solutions for Loneliness

Through a series of practice exercises, Long and Onelio guided workshop participants through three phases of human-centered design: validating the problem with users by discovery interviews and user insight; ideation, or generating and refining ideas; and prototyping.

Loneliness was chosen as a practice topic because many people are familiar with the issue and would be able to ponder solutions. The issue also reflects Ariadne’s project on loneliness done in partnership with New York City health systems. “As designers and public health professionals, we seek to develop a public health approach to prevent and mitigate loneliness across the entire age spectrum,” Long noted.

Breaking up into pairs, the participants – who included medical students, physicians and public health students – interviewed each other about how they experienced loneliness and connectedness. The aim was to try to understand just what loneliness meant, what people need most when they feel lonely, what barriers keep them from getting what they need, and what would be important in a solution. Insights included, “Sometimes I am lonely because I’m not connected to myself;” or “Sometimes I am lonely because I am not really present.”

One participant was blunt: “I don’t think you can prevent loneliness… so my solution [would be] focused on how to help people navigate their way through loneliness.”

The students then worked together to brainstorm ideas that would address those needs and overcome barriers. Then, to illustrate the concept of prototyping, students chose one idea to flush out in more detail to share with the group for feedback.

One participant considered how to bring strangers together. “There could be some app…where if someone is going to a movie tomorrow, they could post about it and others on that forum can hop on, meet up and go together,” they said. Another shared an idea for a website to go to when you’re lonely that would walk you through steps of picking a small change to experiment with. Another participant discussed ways to help medical professionals be less lonely by shifting toward integrated teams. One participant described how coffee shops could offer people the chance to write and send gratitude notes.

For the last exercise in the workshop the participants practiced prototyping ideas. Onelio challenged participants: “What will you do to make it real? Give your idea a name. Talk about your customer. Who would you be branding this for?” The aim was to try to make a solution as concrete as possible so as to gather feedback.

Long was pleased with how participants responded with concrete ideas. “I think the students were really engaged in learning about human centered design, taking an idea and moving it from defining the problem to understanding the user’s needs to ideating, prototyping, and testing,” she said.