SAN DIEGO — Science and technology have improved patient care, but they also have created complexities that may cause needless suffering and increased costs.

During the May 6 Anna Marie D’Amico Lecture, “System Complexity and the Challenge of Too Much Medicine, ” at the opening ceremony of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Annual Meeting, Neel T. Shah, MD, MPP, executive director of the Ariadne Labs Delivery Decisions Initiative and an ob-gyn at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, outlined a goal to reduce the number of Caesarean deliveries by implementing simple solutions to complex processes.

“About half the C-sections we do in the United States today are probably avoidable,” said Dr. Shah, noting that statistics show a 500-percent increase in this major surgery in the last generation or two.

The introduction of electronic fetal monitoring in the 1970s increased C-section rates, but it alone is not responsible for the marked increase over the past 40 years because how fetal heart traces are used hasn’t really changed over the years, he said. Studies can also reliably rule out age-related factors, health-risk factors, multiple birth increases due to IVF, medical malpractice threats, reimbursement issues, or maternal preference as the primary mitigating factors.

Research from the University of Minnesota showed that hospital C-section rates in this country varied between 7 percent and 70 percent, a 10-fold variation. When considering low-risk patients only, the research found a 15-fold variation.

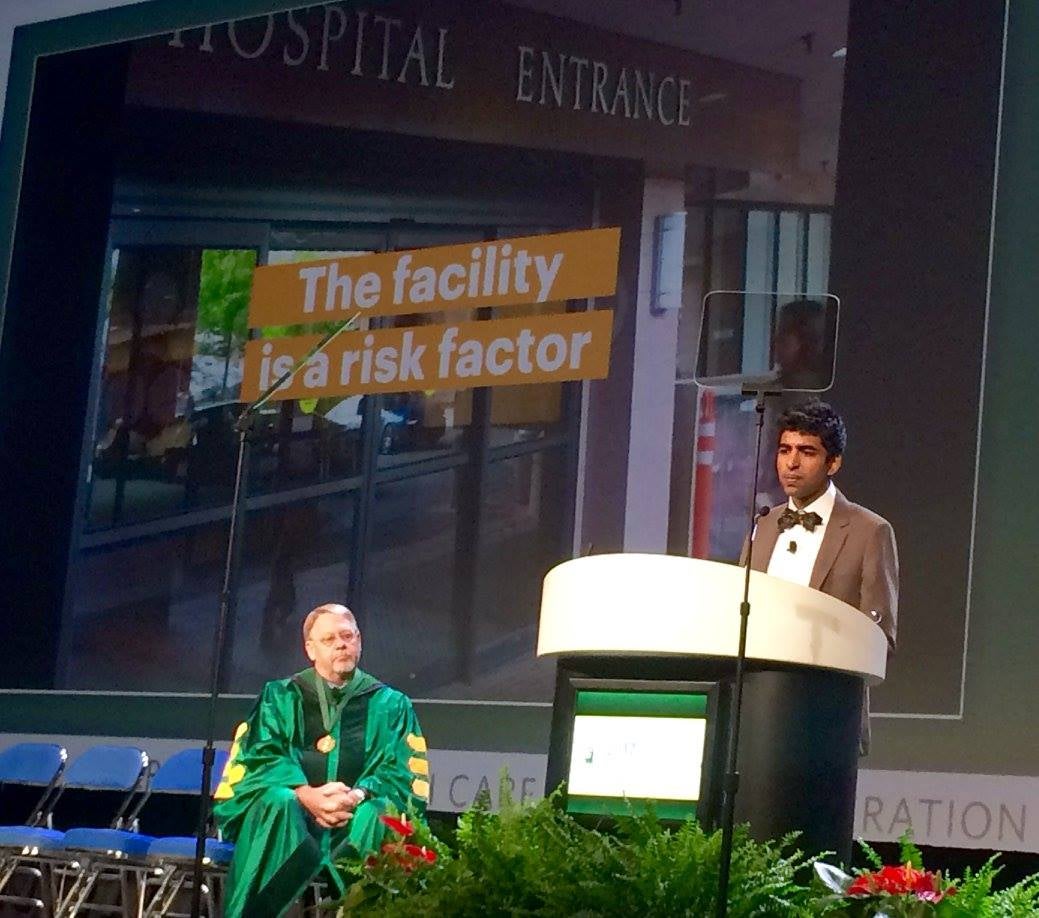

“In 2017, the biggest risk factor for the most common surgery performed on earth is not a woman’s preferences or her medical risks, but literally which door she walks through,” said Dr. Shah.

Dr. Shah and his team looked at data from 53 hospitals and 220,000 patients over two years to determine why some hospital’s C-section rates were so much higher than others to help determine how the number could be lowered.

“Maybe there are things that affect the environment that could make one pathway higher resistance or lower resistance. Most of us are willing to do the harder thing if it’s the right thing, but if you are running out of room, running out of beds, and the writing is on the wall, that might tip the scale,” he said.

Dr. Shah said the study showed that when accounting for every fixed characteristic you can observe about a patient or a hospital, it boiled down to how well a hospital manages complexity.

Simple solutions can combat that complexity.

Using the example of how well the food industry uses labeling to identify various foodstuffs for particular consumers, Dr. Shah noted that obstetrics uses labeling all the time, but maybe not as optimally as possible.

“When you walk into any labor and delivery unit in the country, you can identify the people who are high risk very easily, but the normal people you find by the absence of a label,” he said. “Maybe we could be intentionally identifying the low-risk people when they walk in. That’s what the places that have low C-section rates seem to be doing.”

And hospitals can apply different defaults to them. For example, there are ways of acting that obstetricians all agree on, such as not using continuous fetal monitoring on low-risk women. Most hospitals, however, do the monitoring anyway.

He also noted that it’s time to start forcing function, citing the profession’s tremendous success in reducing 39-week elective inductions. But C-sections can be trickier because they can’t be eliminated entirely.

“According to our own guidelines, we shouldn’t be doing any C-sections on labor progress alone before six centimeters,” he said. “If we just did that, it’s worth tens of thousands of C-sections per year. I believe that’s it’s possible to make things better.”