Ten years ago, a team of medical experts were convened by the World Health Organization (WHO) to achieve a simple yet daunting goal. The WHO wanted to make surgery safer for everyone, everywhere. Not only that, the approach needed to be inexpensive and easy enough to impact millions of lives, in all medical settings. It had to be a solution that hospitals and doctors could implement on their own, long-term, to make the operating room safe from the moment patients arrived.

The WHO tapped Boston surgeon Dr. Atul Gawande to lead the effort, and he invited patient safety expert and cardiovascular surgeon Dr. William Berry. The meeting brought together surgeons, gynecologists, anesthetists, nurses, infection control experts, public health experts, patient advocates and biomedical engineers—the first global meeting of its kind. Their 2006-8 campaign was called “Safe Surgery Saves Lives.”

As the experts iterated on best practices in the OR, they realized that the key to safer surgery globally was grounded in better teamwork and improved communication. So they designed a simple tool that could foster just that—a checklist with 19 essential items that a surgical team needs to perform during every surgery, for every patient.

Today, the tool has been implemented in six continents and touched millions of lives—and there is more yet to do. Ariadne Labs has been at the forefront of this movement: the early team members went on to found Ariadne Labs in 2012, with Safe Surgery as its first program.

In the decade between its development and now, Ariadne Labs has helped implement the tool in diverse settings worldwide. It’s been a journey to understand what works and what doesn’t, and what needs to happen to bring the potential of the checklist into the OR.

Success with the checklist has demonstrated that when it is used correctly, it elevates not just patient care but the entire health system. Communication improves. Professionals feel empowered. And the patient sits safely at the center of it all.

Developing a Global Checklist

Around the world, one out of every 25 people will have surgery every year. Modern medicine has advanced rapidly in the past few decades—doctors can now treat conditions that they didn’t even know about 20 years ago. At the same time, the health care system has become far more complex. Research, treatments, diagnoses and medical equipment are constantly improving, but require updates and training, as well as resources that low and middle-income countries may not always have.

Nonetheless, research has shown that challenges to patient safety during surgery are often the same across countries and settings, regardless of resources. The four most common challenges and barriers to good treatment are: unsafe anesthesia, infection, poor communication in the OR and lack of measurement for surgical results. The WHO team focused on these barriers in developing a solution that could be sustainable.

Berry says, “Most of the debate happened at the first meeting, where we listed all the possible solutions to the problem and really tackled the problem of how to make surgery safer. By our second meeting, the checklist had emerged and it was more straightforward from there.”

Massachusetts General Hospital Surgeon Dr. Alex Haynes, one of the original WHO team members and now director of the Ariadne Labs Safe Surgery program, said the team examined the research on checklists and asked whether such a tool would be effective.

“We wanted to know, would this work for you?” Haynes said.

“There was broad consensus that a checklist could work in this setting—it was really remarkable.”

Checklists aren’t a new concept in medicine, but other industries like aviation use them more consistently and frequently, particularly in emergencies. The WHO campaign aimed to make a checklist that would be become the standard for global surgical care. With this in mind, the working groups identified best practices that would apply for every surgery, and brainstormed how a tool could be brought into a medical setting without causing disruption.

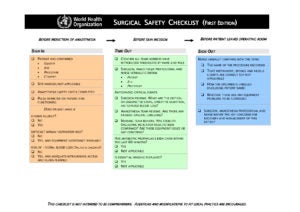

Several iterations later, WHO issued the first edition of the Surgical Safety Checklist in 2008 and the second in 2009.

The 19-item Checklist has three sections that reflect with critical moments during a surgery: before anesthesia, before the first incision and before the patient leaves the OR.

Testing and Implementing

The team began pilot testing the checklist with nearly 8,000 patients in Canada, India, Jordan, New Zealand, Philippines, Tanzania, UK and the United States between October 2007 and September 2008. Researchers were keen to see what might happen when hospitals and other medical environments used the checklist regularly.

The results, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, were dramatic. Patient deaths decreased by 47 percent and complications by 36 percent. Based on the dramatic results of their own institutional work and a strong set of champions, New Zealand has continued to integrate the Checklist in all their public hospitals, with tremendous success.

“It was very validating to have the results we did: we had no expectation of seeing that magnitude,” said Haynes. “I actually didn’t believe the numbers at first, and we did a lot of reverification to make sure they were indeed correct.”

Nearly two years later, researchers in the Netherlands published an unrelated study that showed similarly impressive improvements for patients with the checklist. These two studies boosted awareness of the Checklist and interest in using it around the world.

Other researchers identified what the team already knew: that the Checklist would be most effective when paired with proper implementation. At the University of Toronto, Dr. David Urbach published a study that showed no changes in patient deaths or complications looking at a very broad range of inpatient and ambulatory surgery after a checklist was put in place in Ontario between 2009 and 2010. The checklist was implemented as a mandate with limited training support, demonstrating the limitations of mandates to create change.

In 2010, the team launched the Safe Surgery 2015 program to bring the Checklist to all hospitals in South Carolina. The program became an incubator for the Checklist; team members worked in the state for nearly five years with the South Carolina Hospital Association and local hospitals. The hands-on aspects—webinars, in person meetings, materials, site visits, and office hours—advanced the work. The tool itself became most useful once it had buy-in from administrators and training in the clinic setting.

The South Carolina project produced remarkable results. Deaths after inpatient surgery dropped 22 percent in hospitals that participated in the implementation program; that’s as many lives saved as people killed in car accidents statewide in that time period. Since then, even more hospitals have implemented the Checklist, and about half of the hospitals in South Carolina now make consistent use of the tool.

Spreading the Checklist Worldwide

To support the work of global safe surgery, Gawande founded LifeBox with the World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists (WFSA), Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI), Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Lifebox promotes surgical safety worldwide through partnerships, education, and training. It’s first program worked to distribute to low-income settings the single piece of technology required by the Checklist—pulse oximeters to monitor patient oxygen levels in surgery. The tool is particularly important while a patient is under anesthesia, as small changes in oxygen levels can quickly lead to organ failure and death.

LifeBox has distributed more than 18,000 oximeters in more than 100 countries, typically coupled with checklist training. The tools are implemented with workshops and local training to make both tools effective. In a 2013 study of new pulse oximeter use in Chisinau, Moldova, low oxygen levels decreased by 44 percent and complications decreased by 59 percent.

Dr. Tom Weiser, founding team member and associate professor of surgery at the Stanford University Medical Center, says success can be measured in hard patient outcomes like death and length of stay. Or it can be seen in less measurable but equally important ways.

“The more important impact is almost cultural: the flattening of hierarchy, the idea that surgery is a team sport and all the team members have importance,” Weiser said. “Helping people be humble about their role and accept that they’re there for the benefit of the patient is a really important part. Improvement in attitudes can lead to improvements in care.”

Weiser now leads Clean Cut, a Lifebox program that tackles issues around sterilization, infection, antibiotics and other important best practices before surgery. He says, “My experience is that in resource-rich settings, it’s a behavioral issue. In limited, resource-constrained settings, these gaps are used as an excuse to abandon the checklist. That’s actually a misperception that we’re demonstrating is false. Improvements can be made in any setting.”

Berry added, “The research community sometimes falsely divides high-income from low- and middle-income countries. It takes work to bring change in any setting. These last ten years have taught us the value of persistence and how much time it takes to implement the Checklist. In the U.S. overall, the tool is used variably, but even when it’s not used well, the cultural changes that it brings push people to positive behavior. The checklist has made the practice of delivering antibiotics more effective, for example.”

“These impacts have carried into low- and middle-income settings too,” he said. “In these settings, resources may have to be imported, whereas high-income countries are able to use internal resources. It looks like a more intense effort, but it’s absolutely still possible.”

Beyond the Safe Surgery Checklist

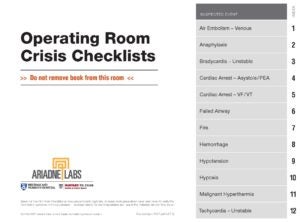

Ariadne Labs now works to disseminate the Safe Surgery Checklist broadly and has added other OR checklists to the portfolio of tools. Since 2012, Ariadne Labs and Stanford University have worked together to form the Emergency Manual Implementation Collaborative (EMIC) to develop OR Crisis Checklists, a compendium of 12 checklists to help OR staff when there are urgent, life-threatening situations during surgery.

For the OR Checklist, the Implementation Toolkit provides basic information for interested hospitals; the Surgical Safety Checklist similarly has best practices that show what truly successful implementation looks like. Ariadne Labs and HSPH also offer a course to help institutions customize, use and roll out checklists in real environments and record webinars for participants who cannot attend in-person trainings. Some of the training is aimed at young surgeons, who will train on the Checklist before they go into a clinical setting.

Ariadne is currently rolling out an online platform called ARIA to support the spread of the Safe Surgery Checklist and other tools. This platform allows clinicians and implementers to communicate with others working with the Checklist, as well as a place to ask questions and get further assistance from professionals. Aria will also allow for a more systematic analysis of what works, what doesn’t and how many professionals are actually using the tool.

Another related Ariadne Labs pipeline project is Digital Phenotyping. The program uses smartphone data to measure a patient’s physical and social functioning (i.e., sleeping, moving around and other “normal” activity) before and after a surgery. Clinicians are good at measuring complications or death following surgery, but it is harder to measure how a patient gets back to full functionality and how long the healing process takes.

By using a digital platform that collects information and sends it to clinicians, Digital Phenotyping measures surgical outcomes that matter most to patients. This program is designed to prioritize patient care after the OR, and eventually Ariadne Labs hopes to scale it worldwide.

After ten years, Haynes said the work around the Checklist itself is still evolving. This essential public health work will only become more important with advances in surgery and technology. “We haven’t cracked the code for uptake in low- and middle-income countries; we’re working on understanding how to implement the Checklist in different environments,” he said. “At the same time, it’s really important to get institutions to make the Checklist their own. We’re also looking at checklists for countries with different levels of income and checklists for different types of surgery. The work continues.”-

–By Katherine Igoe