We found 251 results for your search.

The International Consortium of Newborn Sequencing (ICoNS) published their findings and tool in Genetics in Medicine. They identified key factors influencing gene inclusion in newborn genomic screening programs and the team developed a machine learning model incorporating 13 predictors, achieving high accuracy in predicting gene selection across programs.

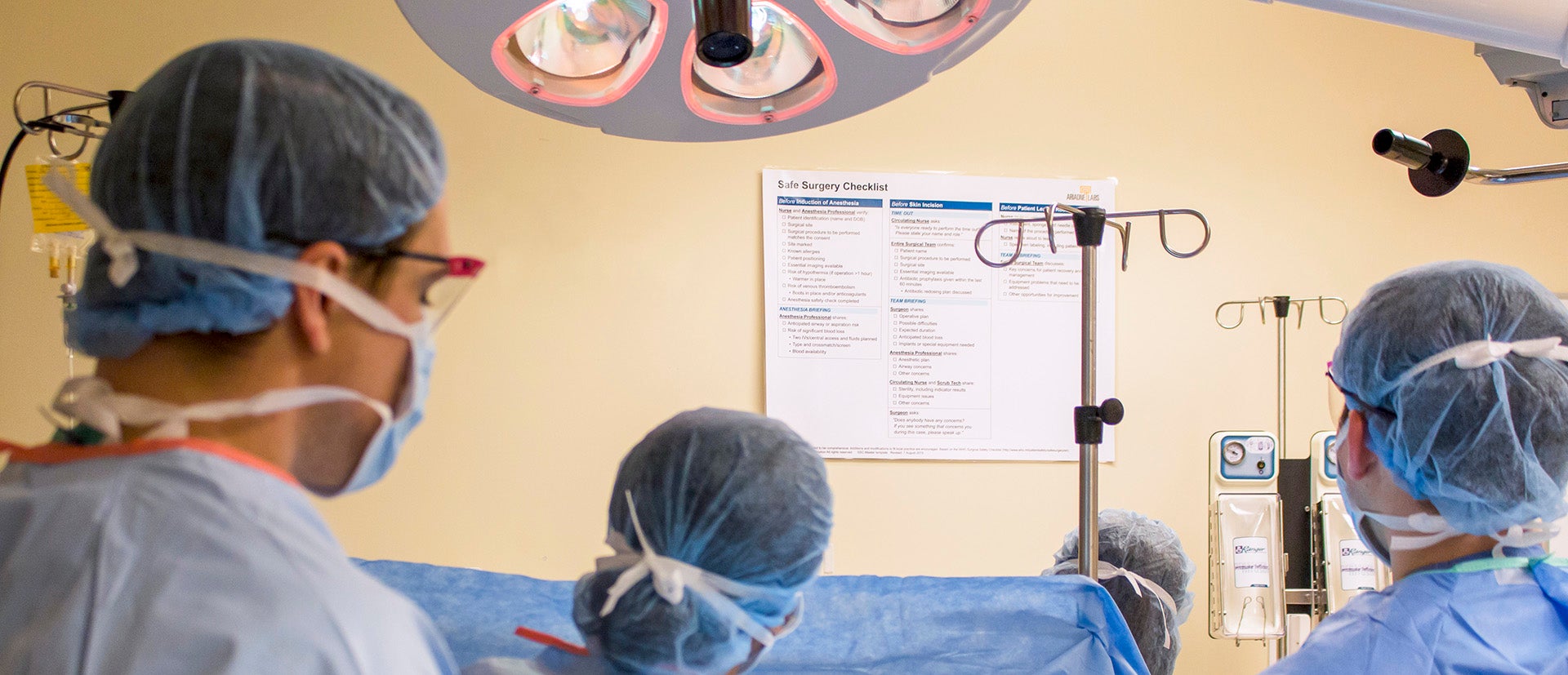

The Safe Surgery/Safe Systems team publish their conceptual framework for team-based morbidity and mortality conferences in The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

Published results from the Spark Grant program’s Cultural Brokering project explores the role that cultural brokers fulfill during pregnancy care for patients with limited English proficiency and the need to recognize, value, and integrate cultural brokering into pregnancy care.

National Academies release new report, co-chaired by Dr. Asaf Bitton, making specific recommendations for CMS, to address the systemic flaws currently affecting primary care professionals and limiting the potential of high-quality primary care services for all.

The Spark Grant-funded Stroke Checklist team published their results on a 2-year quality improvement project co-designed and tested a checklist for quicker evaluation of suspected stroke cases in two emergency departments.

A perspective from participants in the PACT Collaborative published in Frontiers in Health Services on the importance of language in response to patients after they experience harm.

The Innovation Platform developed a clinician tool using human-centered design to enhance communication and trust with Spanish-speaking patients during pregnancy visits.

The BetterBirth team and partners’ systematic review found evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of the Safe Childbirth Checklist in reducing stillbirths and improving adherence to essential birth practices.

The BetterBirth team and their partners published the latest on their research of Manyata, a quality assurance and improvement program that provides training, mentorship and accreditation to private maternity facilities in India.

Drs. Asaf Bitton and Bruce Fink pen a commentary in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine on the steps needed to reorient US primary health care to be more effective, equitable, and efficient.